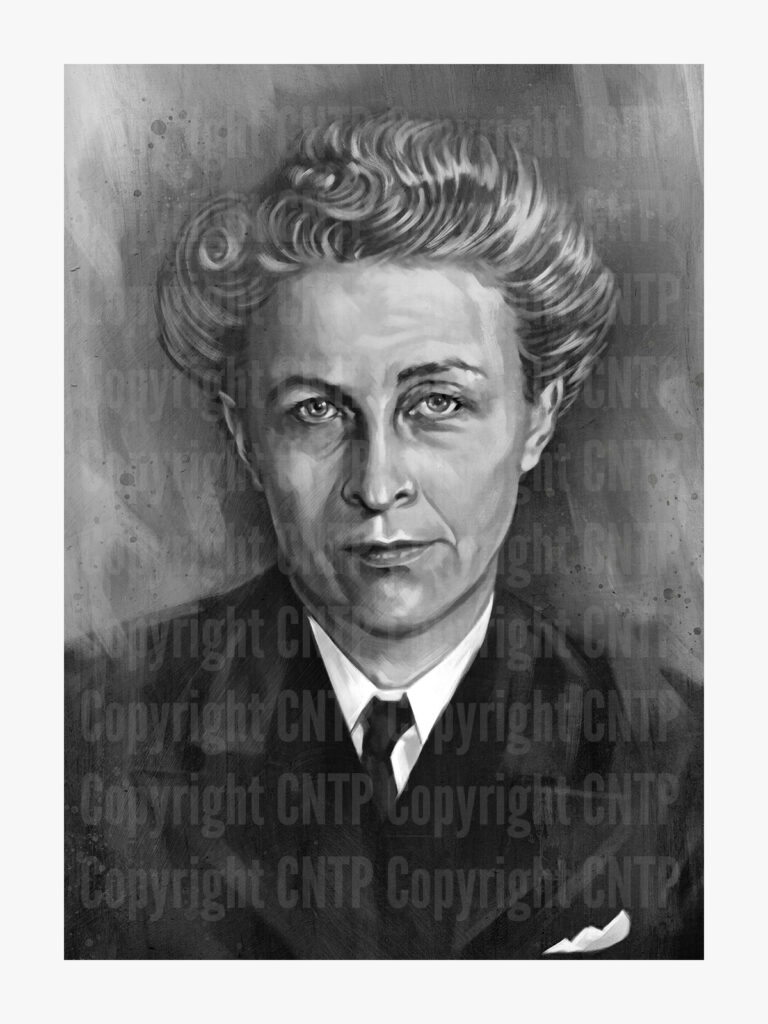

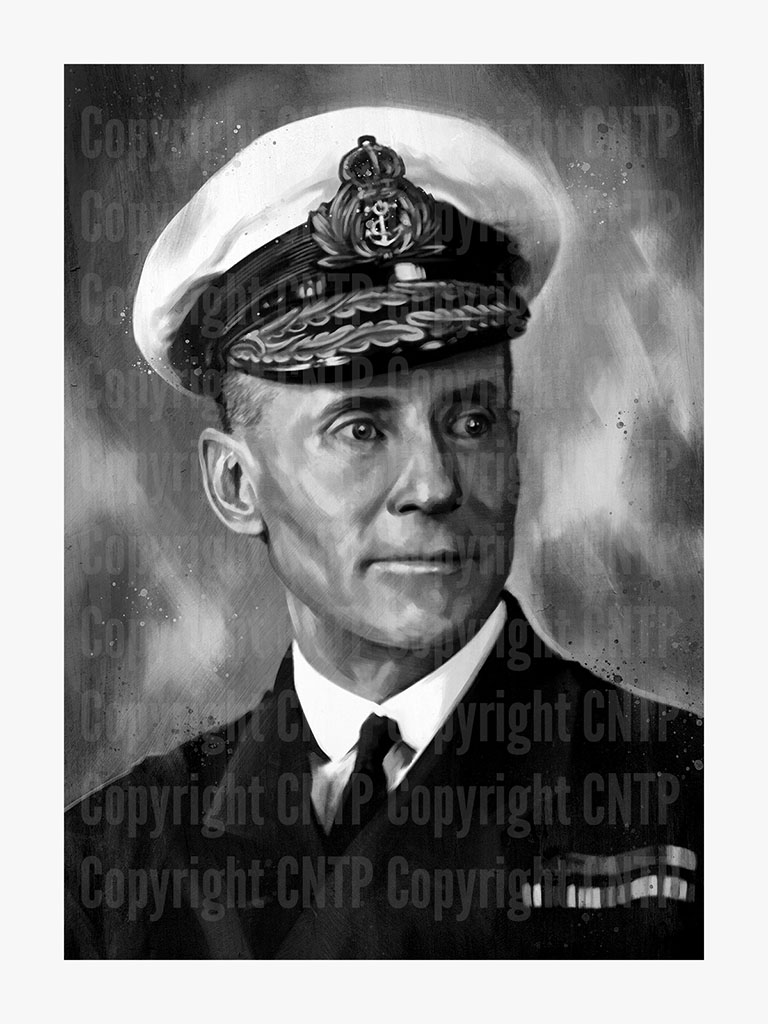

Rear Admiral Walter Hose, CBE, RN, RCNVR

“Saviour of the Royal Canadian Navy and Father of the Canadian Naval Reserve”

The man who would be credited with saving the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) was born on October 2, 1875, while aboard the P&O steamer Surat, mid-transit across the Indian Ocean. In the words of Captain(N) Dr. Wilf Lund, Hose was “quite literally a man of the sea” and destined for a life aboard ship.

Hose joined the Royal Navy (RN) as a Naval Cadet in 1890, and served aboard HM ships Britannia and Hyacinth for his initial officer training. The following year, he moved to HMS Impérieuse in China and, after switching to the Battleship HMS Centurion, was promoted to Midshipman on March 15, 1892 (MacFarlane). In 1894 he served aboard HMS Calypso and was present for the capture of Wei-hai-wei by Japan (MacFarlane). The following year, he was raised to the rank of Sub-Lieutenant, and then went back to England to attend additional training at Greenwich and Portsmouth. While stationed near Dover, Hose was given command of Torpedo Boat 44 and tasked with patrolling the English Channel and performing nautical manoeuvers. He was becoming a solid naval officer, but average in performance. None of his evaluations particularly stood-out in comparison to his peers, nor was his service considered exceptional by RN standards. In the eyes of the Admiralty, Hose was unremarkable.

He was promoted to Lieutenant on December 31, 1897 and was aboard HMS Dragon at Crete during the Turko-Greek war. He then joined HMS Venture in 1898 on China station assuming command of the River Gunboat HMS Tweed and served in the Boxer Rebellion, an anti-colonial uprising sprung by the Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fists (MacFarlane). The English referred to the rebels simply as “boxers” as many were martial artists. For his service in the conflict on the Yangtze River, he was awarded the China War Medal (MacFarlane).

From 1902-05, Hose served as First Lieutenant (or Executive Officer/XO) aboard HMS Charybdis, stationed at Newfoundland for the purpose of training local naval reservists. To Hose, it was yet another standard posting, nothing that would particularly aid him during a promotion board. He’d been growing more and more dissatisfied with this career, and witnessing officers promoted ahead of him made it clear that his prospects of commanding a large warship were growing dim. At this rate, he’d be lucky to make captain, never mind achieving the dream of becoming a flag officer. However, something fortunate did come from his time across the Atlantic – he met Captain Charles Kingsmill, the man who would eventually become the first Director of the Naval Service in Canada. The two developed a professional friendship and maintained regular correspondence. Over the coming years, Hose began to form a plan – a way to advance his career and make his mark on naval history. It would be a decision that would indeed change the course of his career, as well as the future of Canada’s navy.

In 1904, Charybdis travelled south and Hose assisted in the release of British sailors being held hostage in Venezula. Then, in 1905, he assumed command of HMS Ringdove at Newfoundland followed by the destroyer HMS Kale in 1906. He also led the gunboat HMS Redbreast at the East Indies Station and intercepted Afghan gun runners in the Persian Gulf, for which he was personally credited by the Indian Government (MacFarlane). He at last rose to the rank of Commander in 1908 (the rank of Lieutenant-Commander would not be brought-in by the RN until 1914) and, after a year serving as CO of the Alarm-Class Torpedo Gunboat, HMS Jason, he attended the War Staff Course and Combined Naval and Military Operations Staff Course (Nash). Again, Hose passed his courses but without academic distinction. He was subsequently appointed XO the Armoured Cruisier Cochrane in 1909.

Hose had hit a wall in his career, the same one he’d been concerned about for the better part of a decade. He doubted any more promotions loomed in the horizon, and if they did, it wouldn’t be a prime posting. But he wasn’t without a plan. Hose took-up a pen and proceeded to draft a letter to Kingsmill. He’d been keeping abreast of developments regarding the possible formation of a Canadian Naval Service (CNS) and asked his old friend to find something for him. Hose knew that a newly formed navy would need experienced officers to train and develop the fleet, and while he wasn’t considered anything special within the structure of the largest navy in the world, to the CNS, his knowledge and skills would be a great asset. Kingsmill was eager to recruit him, but didn’t have anything to offer at the moment – the Naval Service Act had not yet been passed – but he kept Hose in mind and, in 1911, offered him the opportunity to command HMCS Rainbow (Lund). Hose eagerly accepted and was loaned by the RN to take command of the aged cruiser (Nash).

Although a decent-sized ship, Rainbow was well past her prime. Hose didn’t let that get in the way – he had an opportunity and was determined to seize it. His goal was simple: have Rainbow working as efficiently as any RN ship. The main obstacle was the meager size of her crew. The ship was woefully understaffed and Hose found it hard to keep sailors on deck, never mind replace the ones he lost. It was a problem the fledgling CNS was having across the board. A career in Canada’s navy seemed, at best, risky. There were hardly any ships in the CNS and those it did have were almost all obsolete. A small navy did little to draw applicants or stimulate recruitment. There weren’t any clear career opportunities and, without modern ships and adequate government investment, it appeared the CNS could fizzle-out at any moment. Hose tried his best to sell the program, but watched helplessly as, one by one, numbers gradually fell. By 1913, there weren’t even enough sailors to continue operating the ship, which was forced to stay docked. Government support was also poor and, since most citizens knew little to nothing about the CNS, it was hard to get anyone in the political establishment to take their demands seriously. Simply put, nobody cared, or took the Canadian navy, seriously. Hose realized that he needed to win over the average Canadian to keep the RCN relevant and stimulate confidence in its future.

He made a plan.

When ready, he met with Kingsmill and shared his proposal, suggesting that they establish a “naval reserve with units across the country” (Lund). To his surprise, Kingsmill didn’t agree, replying “My dear Hose, you don’t understand – it can’t be done.” (Lund)

Naturally disappointed, Hose refused to give up on the idea, convinced the plan made sense. After pushing the government, he was given permission to establish a small naval volunteer unit on the west coast in 1914. He sought out support from both the Premier of British Columbia and the Governor General, both who saw merit in his plan. On May 14, 1914, the Royal Naval Canadian Volunteer Reserves (RNCVR – forerunner to the RCNVR) was formed (Lund).

In 1917, three years into the Great War, Hose was made an Acting-Captain and posted to the east coast as Captain of Patrols, specifically tasked with Anti-Submarine Operations in the St. Lawrence (Lund). He jumped into this new role with enthusiasm, pushing himself to the brink and, eventually, collapsing from sheer exhaustion (Lund). He wouldn’t allow himself time to recuperate – there still was a war to win – and he soon returned to work. By the time hostilities ended in 1918, he’d accumulated a wealth of knowledge on managing large-scale naval operations, which helped him to realize what was needed to sustain a post-war Canadian navy. And so he soon found himself going to Ottawa to tackle this very problem – the reorganization of the RCN. This was an entirely new experience for Hose. He was a career naval officer and knew next to nothing about politics (Lund). However, by the beginning of new year, Kingsmill would step-down as Director of the CNS, leaving Hose to fill the gap. Ready or not, the very future of the Canadian navy now rested on his shoulders.

From the outset, Hose set-out to build Canada’s post-war fleet, reaching out to the RN to acquire warships. Travelling to London, he met in person with the Admiralty and managed – through sheer force of will, skill, and perhaps a great deal of luck – to acquire the newly made HMS Aurora for Canada. He also convinced the RN to loan gunnery and torpedo ratings for the ship (Lund). By 1920, HMCS Aurora, Patrician, and Patriot arrived on the East Coast, which Hose intended to use as the start of a small, coastal fleet (Lund). New graduates from the Royal Naval College of Canada were given positions aboard the vessels and things were starting to look promising.

And then everything changed. In 1921, Mackenzie King’s government took charge and immediately began to reduce military expenditures. King’s Liberals weren’t keen on national defence and sought to have the navy brought under control of the Militia. The very independence and identity of the nation’s navy was now in jeopardy.

Immediately, Hose had his funds cut nearly in half, forcing him to reduce the fleet, close the naval college and youth establishments, and reduce personnel to around 400 sailors (Lund). The nation had little faith in its “tin pot navy” and he knew that, without political support, it’s future would be doomed. Again, he considered the question of a national naval reserve – if he could establish them across the country in major cities, it would not only provide jobs but make the RCN visible in areas away form the ocean (Lund).

On January 31, 1923 he formed the Royal Canadian Navy Volunteer Reserve (RCNVR). He had 1000 officers and ratings, which he distributed to units across the country in companies of 50 (Lund). It was just enough to get them going. Thankfully, the public responded well, and recruitment increased exponentially. He was promoted to the Rank of Commodore in August of that year.

The battle was far from over. In 1928, he was officially named Chief of Naval Staff and saw the construction of the first two warships built for the RCN – Destroyers HMCS Skeena and Saguenay. The Great Depression brought more challenges however, including widespread slashes to the defence budget. The Militia was keen to see the navy sink, mostly to aid its own survival – Major General Andrew McNaughton pressured King to abolish the RCN (Lund). Hose stood fast and fought for the navy, his tenacity and spirit wining over the government. In the end, the RCN remained alive, although just barely. Hose was promoted to Rear-Admiral in 1934 and retired from the service, recommending Commander Percy Nelles as his successor. Nellse would be the driving force that would see the RCN blossom during the Second World War.

Hose’s impact on the nation’s history – specifically the RCN – cannot be overstated. If not for his efforts, one wonders how the country would have managed the colossal task of fighting the might of Nazi Germany’s fleet in the Second World War. The Militia had no real intention to maintain a naval force, and if Hose hadn’t been successful, the country would have lacked any skills or equipment upon which to develop a force that could contend with the U-boat peril. As small as the RCN was at the outset of the next war, it still existed. The structure had remained, and new officers and ratings were routinely being trained (most taught by the RN). There were 3,500 men serving in 1939, a combination of regular force sailors and and reservists. And there were operational ships. Granted, they were few – only six destroyers that could serve overseas – but still more than what Hose had when he retired. These ships could immediately begin escorting convoys and provide the necessary buffer upon which to begin the most rapid expansion of any navy in human history.

The importance of still having a naval institution, as well as a collection of experience, skills, and assets – as few as they were – was critical.

The Battle of the Atlantic would be the longest and largest campaign of the entire conflict and, if not for the foundation set by Hose, the country likely wouldn’t have been able to meet the task which fate had firmly set upon its shoulders. If the Canadian “sheepdog” navy wasn’t there, the outcome of the war might have been altogether different. A freighting prospect considering what was at stake.

Hose moved to Windsor, Ontario and occupied himself with wood-working, a hobby he shared with a close friend William LaNauze, who’d later serve in the RCN from 1941 to 1966. He died on June 22, 1965, receiving a military funeral and, quite fittingly, his casket was carried by pallbearers from one of the reserve units he established (HMCS Hunter).

Hose’s Awards and Decorations:

Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE), China Medal, 1914-15 Star, British War Medal, Victory Medal with MiD, the Order of the Sacred Treasure, 3rd Class (Japan).

Sources:

Sabrina Nash, A/Director Navy Public Affairs, email communication with author.

Wilf, Lund. “Rear Admiral Walter Hose: Saving the RCN,” CFB Esquimalt Naval & Military Museum, accessed January 16, 2023, https://navalandmilitarymuseum.org/archives/articles/beginnings/rear-admiral-walter-hose/

John MacFarlane. “The Memorial to Rear–Admiral Walter Hose RCN,” The Nauticapedia, 2017, https://www.nauticapedia.ca/Gallery/Monument_Walter_Hose.php

Prepared By:

Sean E. Livingston, Co-Founder CNTP and Author Oakville’s Flower: The History of HMCS Oakville