“Provided Exceptional Leadership in organizing the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service during the Second World War.”

By: Sean E. Livingston, CNTP Co-Founder and Author

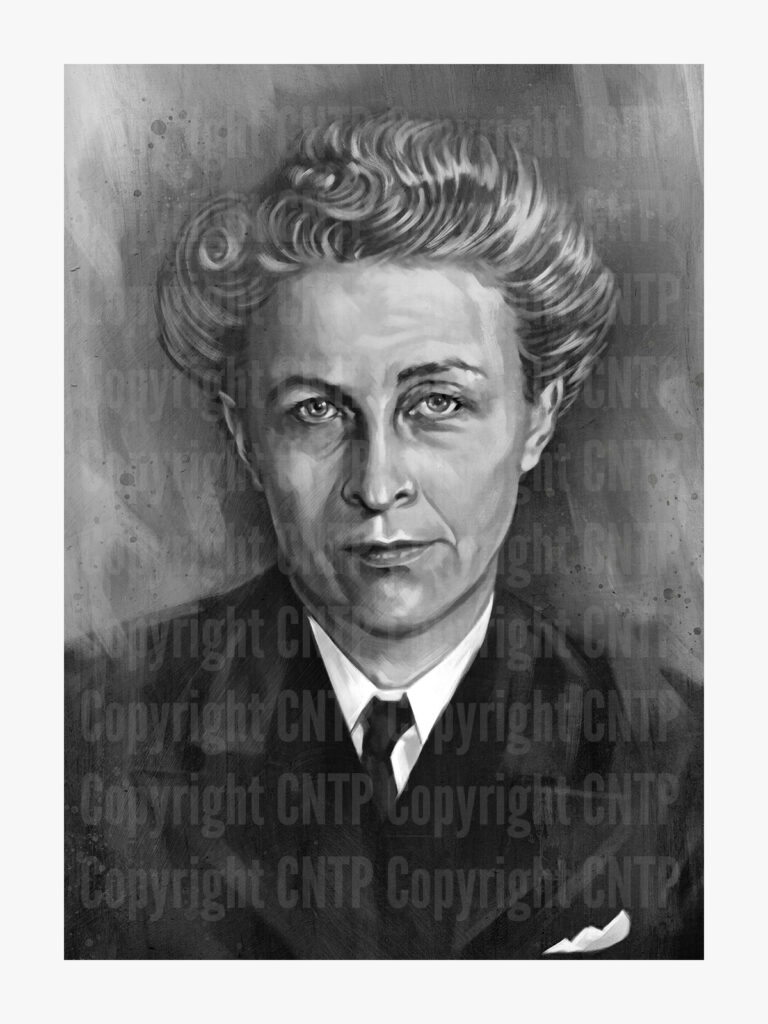

On a cold, mid-January day in 1900, Adelaide Helen Grant Sinclair (née MacDonald) was born in Toronto, Ontario*. It was a unique time – Canada was just over thirty years old and very much struggling to find its place in the world. The nation would undergo many transformations over the next century and Sinclair would be instrumental in cementing a place for women in Canadian society, most notably within the military.

Sinclair benefited from a comfortable upbringing, growing-up in an upper middle-class home. Her father was a physician (he passed less than two years after her birth) and mother the daughter of a successful barrister. As such, money was never an issue and Sinclair was able to attend the exclusive Havergal College, an elite, all-girl, private school founded in 1894. She didn’t squander the opportunity – Sinclair worked hard, committed to excelling in both sport and academics. After graduating in 1917, Sinclair, at the behest of her mother, took a half-year “domestic science” course before enrolling at the University of Toronto. Naturally, she delved into her undergraduate studies and extra-curriculars, managing to obtain high marks while simultaneously captaining the women’s hockey team, serving as president of the Women’s Undergraduate Association, and joining the country’s first woman’s fraternity: Kappa Alpha Theta (Baird & Lurding). By the early 1920s she’d earned both an undergraduate degree in political science and a master’s degree in economics.

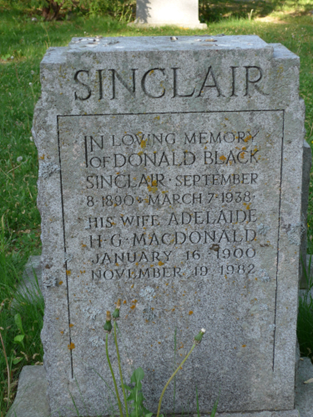

In 1926, the ambitious Sinclair traveled to England to attend the London School of Economics but ended up switching institutions and finishing her studies at the University of Berlin in 1929. With her research and education complete, Sinclair returned to Toronto and worked at her alma mater, lecturing courses in economics and political science. It was during this time that she met and began dating a lawyer, Donald Black Sinclair. They fell in love and on June 7, 1930, were married. They had a close relationship but when her beloved Donald was only 47, he suffered bacterial endocarditis, an infection to the inner layer of his heart. His condition rapidly deteriorated and on March 7, 1938, he died of sudden cardiac arrest. The loss gutted Sinclair. She never truly recovered from his loss and chose to remain a widow the rest of her life.

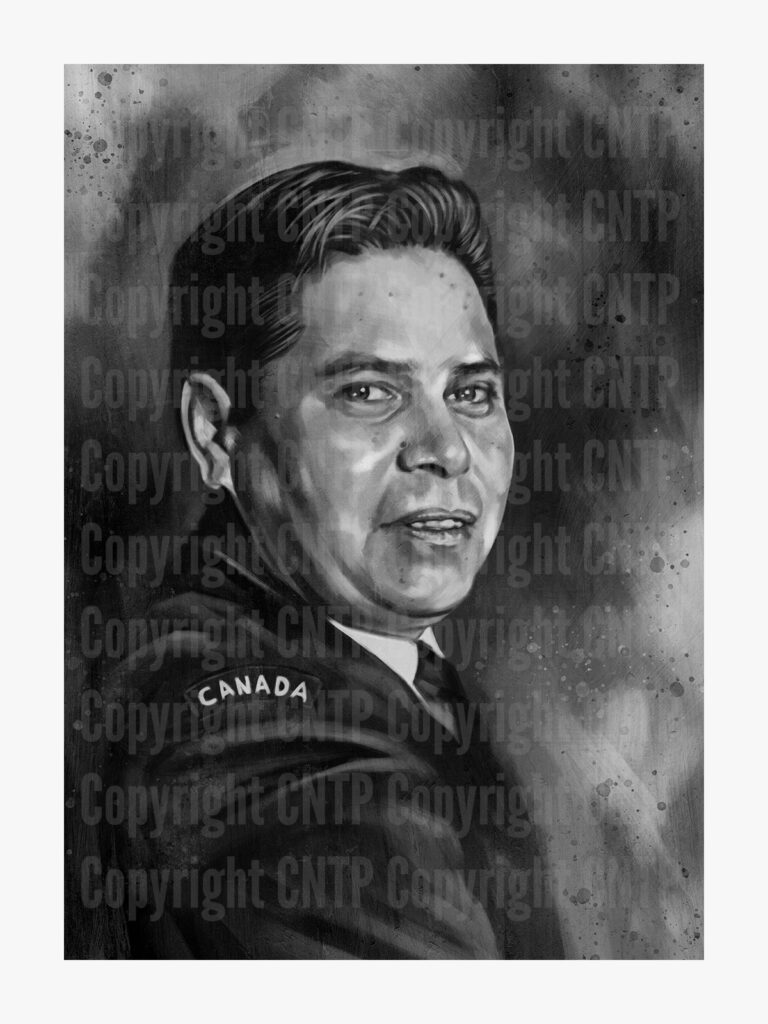

After the outbreak of yet another World War, Sinclair joined the Central Volunteer Bureau and chaired the Women’s Salvage Committee. She moved to Ottawa in 1942 and became an economist with the Wartime Prices and Trade Board (de Bruin). The following year, she joined the newly formed Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service (WRCNS), which had been modeled after the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS, often referred to as ‘Wrens’) in the United Kingdom. Seasoned WRNS officers were sent on-loan to the RCN to assist with the development of the service. As such, the first director was Commander Dorothy Isherwood, who took charge in March 1943, around the same time Sinclair joined. After her basic training, Sinclair’s ambition, leadership abilities, and academic qualifications impressed her superiors who quickly identified her for a future leadership role in the WRCNS. Sinclair was subsequently chosen to head overseas to work directly with the WRNS and learn the ins-and-outs of the organization. She returned to Canada in September, was promoted to Lieutenant-Commander, and took over Isherwood’s post as the new director, the first Canadian to do so. Another promotion to Commander came shortly thereafter.

Although Sinclair’s new role was officially located at Naval Headquarters in Ottawa, she regularly spoke to the media and attended WRCNS stations across the country. While inspecting Wrens at HMCS York in Toronto, Sinclair informed the press that her members were “… on active service in every capacity from cooks to coders”, adding that “Women of the Royal Canadian Navy are on duty in Britain, U.S. Newfoundland as well as at home.” Acknowledging that British Wrens have served in various harbour vessels, Sinclair noted that “It is agreed that waters around Halifax are too rough and stormy; requirements on the west coast are not sufficiently great to make it necessary.” She did point out that “more women are being taken in communications” and that “These Wrens study wireless, coding, cyphering and visual signalling [sic] in the same schools as the men.”

In November 1944, while inspecting Wrens in Newfoundland, Sinclair noted that the WRCNS had grown to 6,000 strong (nearly 7,000 women would serve by August 1945). Many members were eager to serve in greater roles and had requested to be sent overseas beyond Britain. Responding to a query asked by a reporter from the Hamilton Spectator, she indicated “Canadian Wrens have asked me rather subtly if their British sisters aren’t deserving of a rest after five years’ service in Bermuda, Bombay or Australia, but I’m afraid our activities will have to be confined to the United Kingdom and North America.” Having said that, Sinclair had also been considering an expanded role for women in the service, although it was still premature to address that in a public forum. Instead, she towed the line and encouraged the Wrens on parade by saying “bear in mind that you are releasing a man for more active duty at sea, and that is an important contribution to the war effort.”

Both Sinclair and the WRNCS were praised by command. Vice-Admiral G. C. Jones, CB, RCN, then Chief of Naval Staff, stated that “The men of Canada’s navy are proud of the Wrens” and acknowledged “I think it is quite evident that the Wrens are now experienced in the ways of the service and, I am happy to say, they have gained the confidence and respect of the whole service for their general efficiency and tact.” By 1945, Sinclair was given a fourth blue bar to her uniform and promoted to Naval Captain** – the first woman in Canadian history to achieve the rank. She was also made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire in the King’s New Year Honours list, her citation noting Sinclair’s “untiring zeal and outstanding ability, tact and judgement” and that her efforts had turned the WRCNS “into a most efficient and well-disciplined unit” (London Gazette).

While she enjoyed her time with the WRCNS, there were some challenges with being a woman in a man’s world. Even though Sinclair held a senior rank and appointment, women weren’t fully integrated into the military. They were, at best, temporary contract workers and barred from active or combat-related roles. Still, Sinclair wanted to find a permanent place for women in the service. Friend and confidant Jean Gow would later state that Sinclair “… was adamant when fighting for her Wrens and their rights.” Knowing the WRCNS was due to be disbanded after the war, Sinclair authored a report addressing the future of women in Canada’s armed forces. In it, she argued that veteran servicewomen would be needed to facilitate and manage any re-organizing of women in the service in the future. She also expressed that “… wartime experience proved that future servicewomen should be treated like servicemen, except where servicewomen’s gender-specific needs required different treatment.” (Hogenbirk 187) Additionally, Sinclair pushed for an equitable service whereby women would receive equal training and compensation. She stated:

It is hoped that equal pay for men and women may be a commonplace before the outbreak of the war. If not, it is one of the strongest recommendations of this report that it be adopted by the Navy. Part from obvious equity of proposal, the women have proved in this war that they can perform the particularly [sic] tasks assigned to them as well or better than their male counterparts.

Sinclair’s report was shrewdly submitted May 31, 1946, the effective date of her discharge from the navy. As explained by Sarah Hogenbirk in her Doctoral Thesis Women Inside the Canadian Military,1938-1966, “… its submission [was] one of her last acts as Director” and “was Sinclair’s wartime legacy” (188). Decades later, Sinclair would provide a copy of the report to the Library and Archives Canada (Hogenbirk 188).

After the war, Sinclair became the executive assistant to the Deputy Minister of National Health and Welfare, a position she would keep for over a decade. Additionally, the country sent her as the Canadian delegate to the United Nation’s International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) in 1946. Sinclair would remain active with the organization, rising through various positions, and eventually become the executive director of programs, a role she held from 1957 to her retirement in 1967. When UNICEF was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1965, Sinclair was part of the delegation sent to receive the award. She had become “one of the highest ranking and most powerful women at the United Nations at the time” and was awarded the Order of Canada (Officer Grade) for her work with both the WRCNS and UNICEF. Future Prime Minister, The Right Honourable Paul Martin, at the time External Affairs Minister, sent her a letter on behalf of the Canadian government and the Canadian UN delegation, to express “our appreciation for all that you have done for Canada over the years.” Martin also wrote “You are among the select band of Canadians whose contributions to the international organization have given Canada such an enviable reputation.” With the letter was a replica of the Nobel Peace Prize UNICEF had won in 1965, sent with compliments “from the UNICEF staff”. The University of British Columbia also awarded her an honourary legal doctorate in 1968.

Sinclair died on November 19, 1982 and was buried with her late husband in Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Toronto. Harry Black, then executive director of UNICEF, announced the establishment of a memorial fund in Sinclair’s honour, the money donated to an overseas project in her name. The Naval Museum of Halifax produced a bust of Sinclair as part of the 70th anniversary of the WRCNS.

Footnotes:

*January 16, 1900

**It was an Acting rank – Sinclair was still a substantive Commander. Additionally, blue rank braid was used for commissioned members of the WRCNS.

Sinclair’s Awards and Decorations:

The author is in the process of acquiring a complete record of Sinclair’s honours. In addition to being admitted as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire and an Officer of the Order of Canada, Sinclair would have also been eligible for the Canadian Volunteer Service Medal and British War Medal. It’s also possible (and quite likely) that she would have been awarded one or two commemorative medals.

Sources:

Hogenbirk, S. Women Inside the Canadian Military,1938-1966. Doctoral Thesis, Carleton University, 2017.

Plows, E.A. Serving Their Country: The Story of the WRENS, 1942-1946. Canadian Military Review IX:2, 2008.

William Raimond Baird; Carroll Lurding (eds.). “Almanac of Fraternities and Sororities (Baird’s Manual Online Archive), section showing Kappa Alpha Theta chapters”.

Second World War Canadian Navy Lists

Various Newspapers from 1940s and 1980s

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/adelaide-sinclair#

https://onegirlrevolutionproductions.wordpress.com/2015/03/26/adelaide-sinclair/

Prepared By:

Sean E. Livingston, Co-Founder CNTP and Author Oakville’s Flower: The History of HMCS Oakville