Commander Roland Bourke VC, DSO, RCNVR

“Led his Motor Launch through enemy fire to rescue sailors”

By: Sean E. Livingston, Author and CNTP Co-Founder

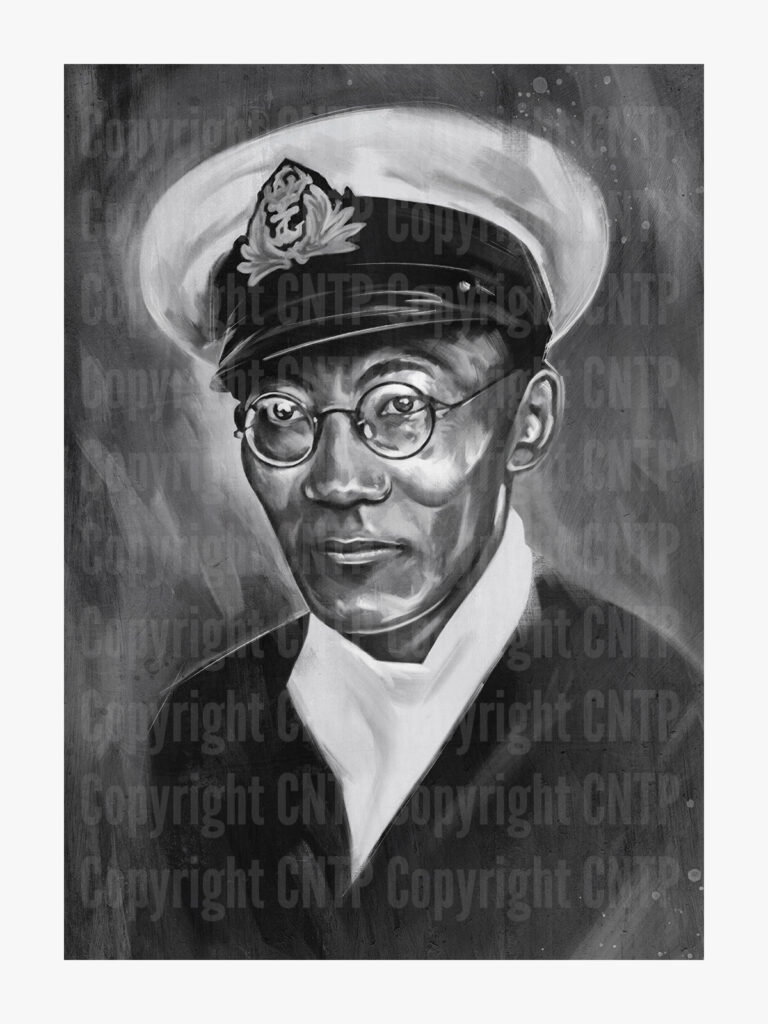

Rowland Richard Louis Bourke was the last person anyone expected to be involved in a war, let alone hailed a hero. Small framed, with disproportionately large feet and thick-lensed spectacles, he looked awkward and decidedly unathletic. It was doubtful he would ever serve in uniform – could he even meet the military’s basic physical requirements? Almost everyone underestimated him, but behind his tiny, meek exterior was a giant of a man who possessed unrivaled courage and grit. Not only would Bourke end up taking an active role in both World Wars, but he would also become of one the highest decorated naval officers in Canadian history.

Born in London, England, on November 28, 1885, he was by all accounts a quiet, kind-hearted youth. Affectionately called “Rowley”, Bourke was the youngest son of a large, mixed family, which included three half-brothers, three sisters, and two adopted nephews. His father, Isidore McWilliam Bourke, was an army regular and saw service in both India and the East Indies before retiring as a surgeon major of the 72nd (Seaforth) Highlanders. He opened a medical practice in Redcliff Square but, near the turn of the century, became obsessed with stories of riches surrounding the Klondike gold rush and decided to try his luck at prospecting. With a few of his eldest sons, he traveled to Dawson, Yukon, conducting private mining operations and establishing the city’s first hospital. Bourke wasn’t permitted to join his father who insisted he first complete his education, but after graduating in 1902, the 17-year-old was finally allowed to join his family in Canada.

After several years gold hunting (like most, they never did strike it rich), Bourke’s father decided to move the family south to a ranch in Nelson, British Columbia, and establish a fruit farm. One day, while helping to clear the surrounding land of trees, Bourke’s adopted cousin, Cecil, was killed in an explosion. Bourke had been there when it happened. Although surviving the blast, he’d been looking directly at Cecil and exposed his eyes to the flash. Doctor’s feared Bourke may never see again, and while he would eventually regain some of his vision, his sight would remain impaired and require the aid of heavy-prescription glasses. Haunted by the accident, the family sold the farm and moved to New Zealand, but only a few years later, Bourke would return to Canada. He was determined to make it as a farmer.

Although nobody disliked him, the neighbours had trouble accepting him as one of their own. Compared to the typical, brawny rancher, he looked out of place, especially with his glasses. The prescription magnified his eyes, giving him an almost cartoonish look. On the surface, there was nothing rough or tough about Bourke, and as a friend would later state, “[Bourke was] a man not strong physically, a man self-deprecating and shy, a man with grave limitations and very conscious of his difference from other men.” (Naval Military Museum) Yet the few that were close to him recognized something unique and special – Bourke wouldn’t let anything, least of all his vision and size, stand in the way of his goals.

When Canada found itself involved in The Great War, Bourke was among the many young men who rushed to enlist. To no one’s surprise, his physical scores were dismal, and he failed the minimum eye examination. The army was particularly concerned with the latter – even Frederick Banting, future Nobel laureate and recipient of the Military Cross for his actions at the Cambrai Offensive, was twice denied entry into the Canadian Army due to his eyesight (the growing need for doctors on the western front would cause the army to relax this requirement and Banting would be granted a commission). Bourke continued to press recruiters, but they wouldn’t change their decision.

It became a bit of a running joke among the locals. To them, Bourke was acting irrational and refusing to accept reality: a man who was half blind couldn’t be a soldier. He would be a liability to both himself and those around him. Still, Bourke refused to quit and decided to try a different approach, donating a substantial portion of waterfront property to the local patriotic fund. He hoped his generosity would pull at some heartstrings and encourage the upper echelon of the army to grant him an exception. It didn’t – unless he could pass the physical exam, they wouldn’t admit him.

Bourke made a new plan, this time attempting to enlist with the newly formed Royal Flying Corps (RFC). Now people thought he was mad – if he wasn’t fit to be a soldier, how could he possibly think of becoming a pilot? Again, he failed the eye examination, scoring well below the minimum requirement, but Bourke believed the test was flawed and set out to prove that he could fly. He enrolled in the American Air School in California and, to his credit, passed the course. Upon returning to Canada, he presented RFC recruiters with his newly acquired flying certificate but, even with a legitimate qualification, they wouldn’t budge on the physical requirement. It was yet another blow, but rather than toss-in the sponge, Bourke turned his sights to a third option – the sea.

The Naval Service of Canada was still in the process of building a fleet, so Bourke decided to travel back to England and apply to the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNVR). By what a friend would later describe as “careless chance”, Bourke managed to be admitted and on January 7, 1916, was commissioned as a Sub-Lieutenant. He was assigned to Coastal Forces and attended training in Greenwich and Southampton. Despite running “…his launch into logs on the lake”, and even crashing “…in full daylight when approaching a wharf”, he passed the course and assumed command of Motor-Launch (ML) 341 in Larne, Ireland.

Over the next year, Bourke led his vessel on routine coastal patrols and anti-submarine operations, all of which were uneventful. He began to suspect that he’d been purposely posted away from the action because of his disability and brought his concerns to command. After some convincing, Bourke’s CO approved his transfer to Dover and in November 1917, he assumed command of ML 276.

Things were very different at his new post. Here the RN worked to disrupt German shipping and frequently entered skirmishes with the enemy. The English Channel was a hotly contested area and Bourke’s vessel was made a rescue launch. Rather than conduct patrols, his job was now to enter active combat zones and save shipwrecked sailors. The possibility of coming under enemy fire was now very real.

In the spring of 1918, the RN moved to implement a scheme to blockade the Belgium ports of Zeebrugge and Ostend. The German Imperial Navy were using these sites to launch U-boat attacks against allied shipping crossing the Atlantic and command decided it was time to cut-off the enemy’s use of these ports. A threefold plan was formed – block Bruges ship-canal at its entrance into Zeebrugge, close sea access to Ostend harbour, and generally “inflict as much damage as possible” (GreatWar) to degrade or neutralize both ports. Vice-Admiral Sir Roger Keyes, the mastermind behind the operation, would use seventy-five ships and over 1,700 sailors to conduct the night attack. Bourke was quick to volunteer but concern arose regarding his eyesight – command wasn’t convinced he could adequately direct his vessel in the dark. Undaunted, Bourke insisted and, through sheer force of will, managed to persuade his superiors to allow 276 to participate.

On the night of April 23rd, the RN launched a dual raid to put both ports out of action. While successfully sinking three, concrete laden, cruisers in the Zeebrugee ship-canal, things didn’t go as planned at Ostend.

It was just after 2300hrs on the 22nd. Bourke was in the MLs tiny, open bridge, binoculars to his eyes. He was following the large, dark shape of HMS Sirius, which trailed in Brilliant’s wake. Both were outdated Apollo-Class cruisers, bows packed with concrete to provide protection from enemy fire and help facilitate the blocking of the harbour when scuttled. The enemy would be hard-pressed to remove these hulks – they would act like steel barriers in the shallow passageway, preventing any vessel from entering or leaving port. Presently, Brilliant was on the lookout for the Stroom Bank Buoy, which marked the mouth of the canal. From there both cruisers, under cover of smoke provided by the MLs and Coastal Motor Boats (CMB), would position themselves at the entrance and run aground. Three MLs would then head in to rescue the crews – 276 was responsible for Brilliant.

Bourke felt a gust across his face and lowered his binoculars. While a calm sea would have been preferable, it was decided that the wind was mild enough to continue with the operation. Poor weather had already forced command to postpone the mission twice and they were keen to get on with things. At least it was blowing away from them, meaning their smoke screen would linger ashore and prevent enemy gun batteries from accurately targeting the cruisers.

So why was Bourke suddenly concerned?

Because the wind had just changed direction. Adding further complications, it started to grow stronger, and he could feel his ML begin to roll with the chop. Bourke now doubted they could adequately use the smoke to protect the cruisers. Although he’d correctly identified these problems, the situation was worse than he realized. Up ahead, lookouts aboard the cruisers couldn’t find the Stroom Bank Buoy. Navigators consulted their charts and double-checked their plots, but the math all added up. So where was the buoy?

The captains concluded they must have drifted to the north and were in the wrong place. It seemed the only sensible explanation. So, they altered course and proceeded towards the coast until they caught sight of the mainland. Two minutes later, a lookout finally spotted the buoy, although it appeared to be in the wrong place and further off to the north-east. Still, the concerns of the navigating officers were dismissed, and the cruisers again adjusted course.

It never crossed their minds that perhaps the enemy had purposely moved the buoy. The ships were now unknowingly heading off course, away from Ostend and into shallow waters, where a series of underwater sandbanks awaited.

It was a trap.

Meanwhile, per the plan, the MLs and CMBs initiated the next phase of the operation and approached the Ostend piers, banking hard and laying a long line of smoke to protect Brilliant and Sirius’ advance. Offshore vessels, including four Lord Clive-class monitors with 12-inch guns, three M15 Class Monitors with 7.5-inch guns, and three destroyers, began pounding the coast to provide cover for the smaller vessels laying the screen. The enemy’s response was immediate, their counter fire aimed at the distant muzzle flashes.

Overhead, Bourke could hear the whistling of criss-crossing shells ripping through the air and kept his boat moving. It was immediately clear that the screen wouldn’t work – the wind, even stronger than before, simply blew it seaward, exposing everyone to what the MLs and CMBs would later report as “heavy, but happily ill-directed, gunfire”. If not for the darkness, the vessels would be easy targets for the shore batteries.

Brilliant and Sirius, without the aid of the smokescreen, began taking fire. Shells tore through their hulls, and a few shots even caused Sirius to take-on water. Despite the onslaught, the ships pressed-on to their objective. At least, that’s what they thought.

By now the smoke screen was upon the cruisers, obscuring their ability to see and forcing Sirius to follow even closer to Brilliant. This unfortunately meant that any shell that overshot the lead ship fell upon her, taring through the superstructure and upper deck. Brilliant was first to run aground. Those aboard were taken completely by surprise and failed to brace themselves as the heavy hull dug into sand. The ship came to a sudden stop, knocking everyone off their feet – they slammed hard into equipment, bulkheads, decks, and other sailors. A break in the smoke allowed Sirius’ captain to notice what had happened and immediately ordered the helm to turn hard over and engines put full astern. Unfortunately, as Sirius was already damaged, the aged ship didn’t respond in time and rammed Brilliant’s port quarter. Both vessels were now grounded “about 2,400 yards east of the canal entrance” (official report on operations 22-23 April, 1918) and vulnerable. Enemy gunners showed no mercy, pummeling each with shell after shell, turning the hulls into perforated slabs of hot metal The crews desperately scrambled to abandoned ship, a perilous feat under the sustained barrage.

Despite being harassed by heavy machine gun fire, 276 and the other MLs remained at the ready. Upon seeing the cruisers run aground, Bourke ordered his vessel to move in. Accompanied by MLs 283 and 532, the three rescue boats closed at speed, feeling the pressure of each shell striking the wrecks. Even a few shore-based machine guns were firing on the cruisers – the small, unarmoured 86-foot MLs wouldn’t stand a chance if they came between the two. Bourke knew he had to come along side to save the crew, but wisely decided to approach Brilliant’s port side so that the cruiser’s hull would shield his ML. However, even with the added protection, and comparatively small profile of his vessel, bullets and shrapnel still peppered his hull.

Just as sailors began to lower themselves aboard, he realized his boat was drifting back towards Brilliant’s stern. The cruiser’s mighty engines were still turning, the spinning screws requiring his helmsman to constantly work the throttle to stay somewhat stationary. They couldn’t simply idle in place, which made it harder to get sailors aboard, especially wounded men who had to be carefully lowered onto the ML’s deck. To prevent his vessel from being destroyed from overshooting shells, Bourke improvised a strategy – 276 broke away, gaining sea room, and then came back along the port side of the ship to pick-up more sailors. He repeated this several times, and in this way rescued the stranded crew.

While the circling manoeuvre minimized damage to his ML, the boat’s freeboard was riddled with holes and some equipment had taken direct hits. Despite the danger, Bourke acted unphased and controlled the urge to duck or flinch. Instead, he stood with his hands clasped behind his back, appearing at all times confident and calm. Of course, it was all an act, but Bourke knew showing any outward signs of fear would shatter his crew’s morale. If the CO wasn’t scared, then all would be well.

As 276 continued its rescue of Brilliant’s crew, 532, blinded by smoke, ended up slamming into Sirius. The impact knocked-out the vessel’s engines and it lingered powerless beside the cruiser. Thankfully, ML 283 was able to embark almost the entire crew from Sirius before heading out to save more from Brilliant who’d managed to lower a whaler, only to have the boat sink upon touching the water.

By this time, Bourke succeeded in rescuing 38 souls from Brilliant, including her captain, Commander Alfred Godsal, who was last to leave. So, he turned his attention to the crippled 532, now besieged by machine guns rounds. Despite the apparent danger, Bourke brought his vessel alongside, tossing over a heaving line to tow the stranded ML. He then pulled 532 away from the cruisers, observing them explode in the distance – the charges, meant to scuttle the ships, had gone off. The distant flames gradually vanished into the night as the flotilla made their way back to Dover.

Despite the botched attempt to seal the port, Bourke’s heroics were not overlooked. He was awarded the second highest decoration for gallantry, the Distinguished Service Order. His citation in the London Gazette read:

Throughout the action showed the greatest coolness and skill in handling his motor-launch. Repeatedly went alongside “Brilliant” under very heavy fire and took off 38 officers and men. Took in tow and brought back to harbour another motorlaunch which was damaged.

The man who many had teased due to his poor eyesight and small stature was now a bona fide war hero. Yet, his story wouldn’t end here. The RN was still determined to cut-off the enemy’s access to Ostend, as well as fully block the port of Zeebrugge (the previous attack hadn’t completely restricted sea access to the U-boat pens) and so, Dover Command decided that they would try again. However, a stint of nasty weather delayed the assault until early May, upon which another force readied to head across the channel.

As before, Bourke was quick to volunteer. Unfortunately, due to a backlog of damaged ships, 276 still hadn’t been serviced. In its present state, the ML was deemed unseaworthy and couldn’t be cleared for duty. Not wanting to miss out, Bourke offered to relinquish his command and join ML 254 as one of its officers. Instead, his CO made a concession: if Bourke could find a volunteer crew, as well as arrange to have his boat fixed well enough to pass a safety check, 276 could act as a standby during the operation. The trick was he needed to somehow accomplish both within 24 hours – there was finally a break in the weather and command couldn’t afford any further delays. Incredibly, Bourke managed to get his vessel refitted and crewed in time for the mission.

On the evening May 9th, ML 276 followed the Arrogant-class cruiser HMS Vindictive and the Apollo-Class cruiser HMS Sappho into the channel. It was a similar plan as before: move during the hours of 2130-0300hrs, block the ports, and retreat no later than 0200hrs so the dark would shield their escape (Gibson). A force of eighteen MLs and ten CMBs accompanied the two block ships. Additionally, they were joined by seven monitors, protected by eight destroyers, two MLs and two French Motor Boats (Gibson). Reports indicated that German destroyers could be operating in the area, so another dozen RN destroyers joined to the flotilla (Gibson).

Shortly after 2100hrs, they commenced the two-and-a-half-hour trip to their targets. At 2245hrs, the force arrived at Dunkirk to form-up and was joined by some RAF bombers. Commodore Lynes assumed command of those assigned to Ostend and, less than an hour after arriving, the raiding fleet and aircraft were once again on the move. Unfortunately, just before midnight, the aged Sappho suffered problems with one her boilers and was forced to withdraw. Lynes decided to push on with only Vindictive as a blockship.

The Germans had removed all markers around the port, but this time the British were ready and had vessels place calcic-phosphide lit buoys to guide the drop ship. They wouldn’t make the same mistake twice. Around 0137hrs, the MLs and CMBs commenced dropping a smoke screen to shield Vindictive’s advance, and, at 0143hrs, the monitors and aircraft began attacking the harbour, targeting key defensive positions and batteries.

276 sped back into the darkness, putting sea room between the ML and the enemy guns. Once they reached a safe distance, Bourke instructed the vessel to come about and slow – they’re job was to wait until the cruiser was in position. As the bow settled, he peered over the bridge screen to observe the battle. The discharge of each gun appeared like hazy, orange shapes. If his eyesight wasn’t damaged, he would have glimpsed details of ships and shore batteries with each flash of light. Sounds of explosions traveled through the air, like thunderclaps in a rainless storm. Not withstanding his diminished sight, it was a breathtaking spectacle of violence and power.

276 felt even smaller in comparison to these larger warships and their impressive arsenal, but his ML was supposed to be small. The strength of coastal forces rested in the speed, maneuverability, and small profile of their vessels which, particularly at night, made them nearly invisible. One couldn’t hit what they couldn’t see.

While they waited, Bourke wondered if things would be different this time. Their previous attempt was an utter failure – not only were they tricked by the enemy, but the weather also betrayed them. At least the latter appeared to be cooperating tonight. There was hardly any wind, and it didn’t blow seaward, meaning that their smoke screen stayed in place, obscuring what little the shore gunners were able to see. Bourke felt relieved.

It was short lived. Around five minutes later, a fog began to drop, quickly building around his boat and reducing visibility to but a few yards. Now the blockship, still 12 minutes away from the opening of the canal, was moving blind. Her destroyer escorts were forced to deploy star shells to help illuminate a path through the mist, which of course alerted the shore batteries. At 0200hrs, Vindictive began taking fire, although she was nearly at her destination.

The ship’s CO, the same officer who commanded Brilliant during the first raid, tried to relay a message to the after control but realized that a shell must have damaged the connection. Godsal decided to relay the orders in person, directing the helm to move hard-a-starboard before he proceeded down the ladder. At that very moment, a shell exploded against the tower, shaking the occupants, and seriously wounding an officer. A few searched for Godsal but soon determined that he’d been at the point of impact – his body was never recovered.

Vindictive “grounded at an angle of about 25 degrees to the eastern pier” (Keyes Report) and the order was promptly given to abandon ship and blow it up where she laid. Burke watched as the upper structure of the blockship fell to enemy fire and knew it was time to move. Both he and ML 254 throttled up and headed for the wreck, fully entering “the fire zone to effect the rescue” (Lynes Report). Lieutenant Geoffrey H. Drummond RNVR brought 254 alongside Vindicitive’s inshore side, taking on 38 survivors. His ML was riddled by deadly machine gun fire, killing both his First Lieutenant and a deckhand while leaving several crew members, including the coxswain, wounded. Drummond was himself hit three times and quickly ran his ML back out to sea, rounds still ripping through the stern. Miraculously, 254 managed to limp clear of the canal’s entrance, but the vessel was too damaged to make it home. It would later sink, but not before the crew and survivors were picked-up by HMS Warwick.

Bourke did what he could to cover 254’s retreat, focusing his own guns on both piers as he sped towards the doomed Vindictive. He was unsure if all had been rescued and brought his ML alongside, shouting for survivors as bullets began piercing his hull. None answered and so he began to sweep the nearby waters, doing what he could to evade enemy machine guns while searching for bodies. Splashes erupted all around, and more rounds found his boat. After a prolonged search in extremely hazardous conditions, Bourke happened across capsized skiff. An officer and two ratings, all badly injured, clung for dear life. Despite needing to bring his vessel right along side, fully exposing himself to the enemy, 276 came up and successfully pulled the three men aboard as bullets sprayed against the deck and near the bridge. Bourke gave the order to head back out to sea and, despite having suffered fifty-five direct hits on his vessel, 276 eventually met another ship who took them back to Dover in tow. Sadly, two of his crew were killed during the rescue, while another wounded when a 6-inch shell exploded near the hull, causing “considerable damage” to the ML.

For his “gallantry and devotion to duty” (London Gazette 27 Aug 1918, issue 30870), Bourke was awarded the highest honour in the Commonwealth, the Victoria Cross (VC), by King George V. Additionally, he was presented with the French Legion of Honour. When writing to his parents to inform them of the news, he asked that they “not to inform the press of his achievements” (Naval Military Museum) to avoid drawing too much attention to himself.

Bourke continued to serve until the end of the war in 1919 before heading back to Canada. In all, the man who’d been rejected so many times by the military, managed to be awarded a VC, DSO, Knight of the Legion of Honour, a Mentioned in Dispatches, and a promotion to Lieutenant-Commander (seniority backdated to April 23, 1918), all in a six-week period. He settled once again to Nelson, British Columbia and the cottage his family still vacationed at. There he discovered that his parents had received a letter from a family friend, Lieutenant Coningsby Dawson, back in September of 1918. In it, Dawson wrote “Did you see the good news concerning R. B. [Bourke]? He’s got his V.C. for saving life under shell-fire in Zeebrugge harbour. His M.L. was hit fifty times.” Dawson went on to recount how: “People laughed that he [Bourke] should offer himself as a fighter at all, but he elbowed his way through their laughter to self-conquest. That’s the grand side of war – its test of internals, of the heart and spirit of a man! Bone and muscle and charm are only secondary.”

Dawson, clearly impressed and proud of his friend, observed, “…he’s the type of hero this war has produced – a man not strong physically, a man self-deprecating and shy, a man with grave limitations and very conscious of his difference from other men. This was his chance to improve himself.” He concluded by stating “Before the war he was the kind of chap with whom girls danced out of kindness. Today he’s a hero.” (Jastrzembski)

Bourke left the service and turned his attention back to farming at his orchard. On September 24, 1919, he married his old sweetheart, Rosalind Thelma (Linda) Barnet in South Vancouver. Born in Australia, she was an accomplished musician and had corresponded with Bourke throughout the war. He proposed to her in a letter he sent after the first Ostend operations, promising that he would marry her “as soon as the war was over”. The Navy League arranged to have Bourke and his wife go on a promotional tour of Australia and New Zealand before they finally settled on the farm in West Kootenay. They would spend the next decade there.

Bourke’s eyesight didn’t improve. By 1931 his vision had become so poor that he feared he’d soon go completely blind. Farming now proved too much of a challenge for him and so they moved to Victoria the following year. Bourke managed to secure a Federal job with the civil service, on staff to the RCN dockyard at Esquimalt (it likely didn’t hurt that he was ex-navy and a highly decorated hero). As the 30s waned and threats of another global conflict loomed on the horizon, Bourke was asked to help establish a “Fishermen’s Naval Reserve” to assist with coastal patrols and security along Canada’s west coast. After the country declared war, the navy felt having a VC winner would greatly assist with recruitment efforts and Bourke was brought into the Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve at his previous rank of Lieutenant-Commander.

In 1941, after a stint working as a recruiting officer, he went back to sea commanding small vessels. He was then promoted to Commander and proceeded to take command of HMCS Givenchy in Esquimalt, followed by Burrard in Vancouver – both cities were given separate Naval Officer’s in Charge in order to allow the Commanding Officer Pacific Coast to focus on naval operations at sea. He stayed in the RCN post-war, finally retiring in 1950.

He was invited to attend the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953 and then, three years later, was brought back to London for the VC Centenary Celebrations at Hyde Park. Less than two year later Bourke passed away at his home in Esquimalt on August 29, 1958. He was buried with full military honours at Royal Oak Burial Park, Victoria, and his medals were bequeathed to the National Archives in Ottawa. They are on display at the Maritime Museum of British Columbia and CFB Esquimalt Naval Museum, along with a pair of his glasses. They remain both a testament to his courage and resilience.

Bourke’s Awards and Decorations:

Victoria Cross (VC), Distinguished Service Order (DSO), British War Medal, Victory Medal with MiD Oakleaf, Canadian Volunteer Service Medal, War Medal, King George VI Coronation Medal, Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal, and Chevalier of the Legion of Honour (France). The engraving on the reserves of his VC reads:

LIEUT-CDR. R. BOURKE. D.S.O.

R.N.V.R.

9 – 10TH

MAY

1918

Sources:

Crowsnest magazine Vol 10. No. 12 Oct 1958

http://www.victoriacross.org.uk/ddcalibr.htm

http://www.vconline.org.uk/rowland-r-l-bourke-vc/4585989365.html

https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Bourke-1048

http://www.greatwar.co.uk/battles/yser/zeebrugge-ostend-raid.htm

https://warandsecurity.com/2018/07/11/the-ostend-raid-9-10-may-1918/

https://www.naval-history.net/WW1Battle1804ZeebruggeOstend.htm

Jastrzembski, Frank. Victoria Cross Heroes: Rowland Bourke History-War, September 6, 2018.

Prepared By:

Sean E. Livingston, Co-Founder CNTP and Author Oakville’s Flower: The History of HMCS Oakville