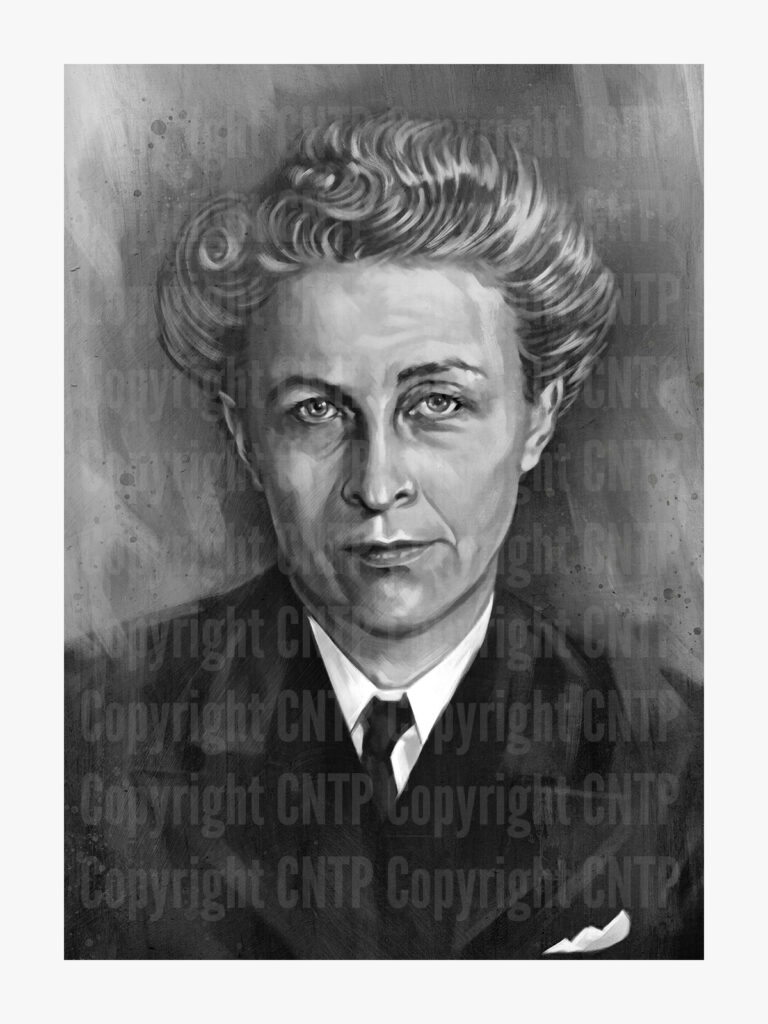

Lieutenant-Commander John Stubbs DSO, DSC, RCN

“Naval prodigy and master tactician who exemplified devotion to duty”

The death of Lieutenant-Commander John Hamilton Stubbs might be the single greatest loss of the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) during the Second World War. A naval prodigy, possessing unrivaled seamanship skills, he seemed to have it all – good looks, intelligence, charisma, health, courage, and natural leadership. His peers and subordinates loved him, while those higher up the chain marveled at his brilliance. Perhaps nobody summed-up his promise better than HMCS Haida’s eight Commanding Officer (CO), Captain (N) Dunn Lantier, who served under Stubbs as a lieutenant in HMCS Athabaskan. Lantier had a reputation for being a tough, matter-of-fact senior officer, who said little and spared even less praise. Yet, when asked about Stubbs, he uncharacteristically stated “He would have gone straight to the top,” further elaborating that he was “… destined to be Chief of Naval Staff.” (Stewart)*

War exacts a heavy toll and perhaps its greatest costs is that it robs the world of our very best.

Stubbs was born on June 5, 1912, in Kaslo, British Columbia, a picturesque mining town located along Lake Kootenay. His father, who he was named after, was an electrical engineer and enjoyed taking his family fishing on weekends and holidays, exposing his son to sailing from the very start. Stubbs became drawn to the water and “…the origin of his exceptional ability in steering and navigating warships can possibly be traced to his early days as a boating enthusiast on the nearby lake” (Burrow & Beaudoin). At the age of ten he joined the Kaslo Sea Cadets which further developed his seamanship skills. Stubbs was a natural, and it was clear to his instructors that the young man had a promising career as a sailor. In his spare time, Stubbs preferred to spend time on the lake alone with his dog Quest at his side.

After his family moved to Victoria, and he completed his schooling, Stubbs applied to the RCN to become an officer. The Headmaster of Brentwood College supported his candidacy, noting that “… his character has been excellent and his industry exemplary.” (Service File) He wrote the naval entrance exam over three days in early May and passed with a 77%**. Then, on May 12, 1930, he was interviewed at the RCN Barracks in Esquimalt and impressed the three Lieutenant-Commanders who conducted his board. They reported that “this candidate is of good appearance, looks strong and healthy; possessing good manners, self assurance and personality”, additionally noting that he “is good at games.” (Service File) They concluded “… that he would make a very good Naval Officer and strongly recommends his entry as Naval Cadet” (Service File). Commander Leonard Warren Murray RCN***, the senior naval officer at CFB Esquimalt, singed-off on the board’s findings, pointing out that Stubbs, in comparison to the other candidates, was “outstanding” and “above average” (Service File). At the age of eighteen, he became a Naval Cadet and took his first steps towards a career at sea.

After completion of his initial training, he was sent overseas for his formal naval education with the RN and was sent to the Mediterranean Fleet. Between 1934-35, he served aboard various HMS ships and shore establishment, obtaining qualifications in Seamanship, Torpedo, and Gunnery. On June 27, 1935, while posted to the battleship Revenge, he obtained 2nd class certification in seamanship, scoring a 739/1000 behind Midshipman M.A. Medland RCN who achieved 853.

In 1935, Stubbs, became the navigation officer aboard HMCS Skeena and on May 1, 1936, was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant. The ship’s CO, Commander D. West, noted Stubbs’ talents and requested that he receive specialist navigational training (aka Long Navigation Course) at HMS Dryad in England. The skills he learned greatly enhanced his seamanship abilities, contributing to his growing reputation as a superb ship-handler and tactician. After the course, he joined HMCS Ottawa in Halifax and was serving as the navigation officer when the Second World War began.

In February of 1940, he took some leave and, at the age of twenty-seven, married his sweetheart, Ruth Moore, on the 28th. There ceremony was held at St. Mark’s Church in Halifax, witnessed by Captain (N) G.C. Jones RCN and his wife (Service File).

On April 3, 1940, he became First-Lieutenant (executive officer or XO) aboard the River-Class Destroyer HMCS Assiniboine, commanded by now Commodore Murray, the same officer who approved his admission into the RCN as a naval cadet a decade earlier. When Murray was posted to the Canadian Naval Mission in London on September 20th of that year, Stubbs assumed command of the ship “As S.O. [Senior Officer] Flotilla (N) duties & as S.O. (O) spare C.O. Destroyer Flotilla” (Service File). It would be while in command that Stubbs would truly shine.

As the new CO, one of the first things Stubbs did was to adopt a stray mongrel and make it the ship’s mascot. For the next two years, Stubbs would escort convoys across the North Atlantic. Despite the harsh demands of these escort duties, the new CO handled it with the calm and ease that would define his command style. As noted by historian Michael Whitby, Stubbs “…grace under pressure was one of his most respected qualities.”

During the famous battle between Hood and Bismarck on May 24, 1941, Assiniboine was not far off when the RN flagship fell to the German hulk. When Churchill’s order to “sink the Bismarck” was received, the Canadian Destroyer was one of the first vessels to pursue, although diminishing fuel supplies forced Stubbs to turn his ship back to port.

The next month, on June 3rd, Stubbs was again crossing the Atlantic, now SO for warships escorting ONS-100 west. Assiniboine was the only the Canadian vessel on escort, the others all being RN and Free-French corvettes (Milner 117). The first few days of the journey were uneventful – nothing much happened, and the seas were relatively calm for the area. However, around 0200hrs on June 9th, the first signs of danger emerged. The convoy was heading west-southwesterly at seven knots when several explosions rang out through the night. Stubbs looked to the starboard quarter of the convoy, the direction the sounds had come from, and swept the area with his binoculars. He couldn’t see anything. No fire or apparent damage to any of the merchant vessels, which was a good thing. Assiniboine then received a message from the Admiralty – U-boats were in the area and suspected to be following ONS-100 (Milner 117).

“No kidding,” he likely thought.

Stubbs waited a few minutes but received no reports of contacts or damage sustained by the convoy. He suspected that U-boats had attacked but had misjudged their distance. The torpedoes detonated short of their targets, having ran-out before coming close to the merchant ships. A few minutes later, several other explosions convinced him his theory was correct and, at 0215hrs, one of the escorts reported radar contact (Milner 117). Stubbs moved quickly, sending orders to the escorts to execute “Raspberry”, a pre-arranged tactic to discover the unseen U-boat. On his command, the warships moved to illuminate with starshell “… a specific sector of the convoy for a prescribed time [and] turn night into day and expose the attacker as he attempted to make good his escape on the surface.” (Milner 117) Each ship did as directed, but the sweep yielded no sightings.

Later that morning, as the sun crept over the horizon, Stubbs was alarmed to see that one of merchant vessels was missing. He immediately turned Assiniboine about and headed to the rear of the convoy, finding floating wreckage and a mere four survivors, which they promptly rescued. U124 had managed to hit the ship with two torpedoes, which was oddly not reported to Stubbs.

Further warnings came regarding U-boats stalking ONS-100. It all became quite clear to Stubbs – they’d have to fight through the “Black Pit” to make it in one piece. Making matters worse, none of his warships were equipped with Huff-Duff (aka High Frequency Direction Finding) which could determine the location of a U-boat based on the high frequency radio transmitters used by the enemy. Rather than despair, Stubbs decided implemented an American tactic, ordering the escorts to patrol at “visibility distance on the port and starboard beams in order to push away U-boats attempting to take positions ahead of ONS-100” (Milner 118) It was his hope that by moving further out, he would force the U-boats to adjust their positions to avoid being too close to the warships.

At 1515hrs, one of the corvettes sighted a U-boat and moved to intercept. Stubbs ordered his vessel to join and together the launched depth charge patterns. While this was happening, word came that another U-boat was on the other side of the ONS-100. The wolves had circled the convoy and were moving in. Stubbs ordered the corvette that made contact to chase-off the enemy well away from the group while he and the other escort broke-off their attack and resume their escort posts. The sun was just starting to set and with it, a fog began to form around them. Although they’d pushed-back two U-boats, the one corvette would only return twelve hours later. (Milner 118) Unbeknownst to Stubbs, one U-boat, commanded by a seasoned captain, had remained close to the merchant vessels, waiting for the cover of night before attacking. Otto Ites directed U94 (the same U-boat that HMCS Oakville would later sink in the Caribbean Sea) through the dense haze, using the cover to sneak past Assiniboine’s stern and firing a torpedo into two ships. It was 0139hrs and Stubbs, knowing the fog would make a Raspberry ineffective, pulled on a “contingency plan for an organized search in low visibility without the aid of illuminants” (Milner 119). U94 decided to slip away from ONS-100 while the opportunity remained.

By daybreak of June 10th, the convoy was nearing the edges of the “pit” and allied air cover. Stubbs knew if they could manage to survive a few more days, the remaining ships would be make it. It was a tense journey but the whole time Stubbs managed it with a self-assured calmness that put everyone at ease. Although still a young Lieutenant, his demeanour and skill made him seem like a seasoned four-ringer. By the 11th, U94 returned with U569 to resume the attack (they had momentarily lost contact with ONS-100). Stubbs didn’t allow the day of inaction to drop his guard. His instincts told him the enemy would strike again and so he kept everyone on high alert. The U-boats targeted a smaller merchant vessel to the rear of the convoy, sinking the ship but then two Canadian ships, Orillia and Chambly, met ONS-100, bolstering the escorts (Milner 119). The next day a final ship was sunk until the convoy finally had air support from Newfoundland. Only then did Stubbs allow himself to relax. His efforts were key in ensuring that only four merchant vessels were lost despite repeated attacks from U-boats.

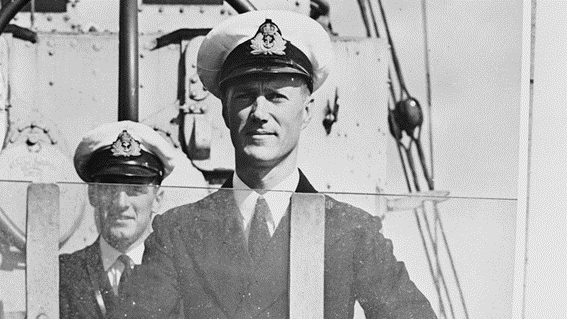

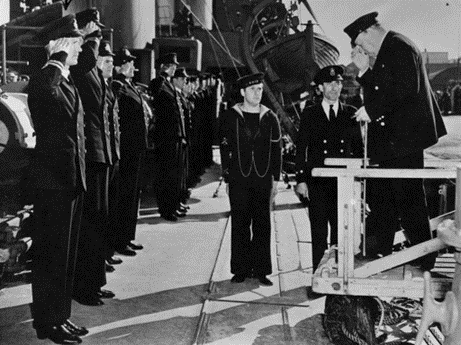

In August, Assiniboine had a special guest come aboard. The Atlantic Charter had just been signed and Prime Minister Winston Churchill boarded the destroyer for an inspection. He was very interested, going through “from stem to stern, pleasantly commending her company for their good work (Burrow & Beaudoin). Later that day, Stubbs received word that “The Rt. Hon. Winston Churchill was most impressed with your handling of HMCS Assiniboine” (Burrow & Beaudoin)

Stubbs’ most famous engagement of the war occurred the following summer. On August 6, 1942, while escorting SC-94, he engaged U-210 in a gritty, close-quarter fight. The account is already listed in some detail under the CNTP biography of CPO Bernays, but what follows is Stubbs’ own accounting of the famous encounter:

We caught up with the U-boat after chasing it in and out of fog and losing sight of it twice. We saw him again at half-mile range and tried to ram but lost him in a fog bank. Then we saw him again, right on the surface and almost a stone’s throw away. We closed him at 200 yards and the submarine started an evading action. We kept moving in and just missed ramming his stern. I was so close we couldn’t depress our guns but we were firing anyway. Then we drew parallel with him and the guns started to boom in earnest on both sides. From my perch on the bridge, I could see the German commander plainly in the conning tower but a short time later he was killed by a shell from one of our 4.7s. The Nazis concentrated their fire on our bridge and the first few shots started a fire on the starboard side. This interfered with our fire-control and so we had to resort to quarter firing, each gun operating independent of the other. With all our guns blazing, our point-five gunners kept spraying the submarine decks. The crew stuck by their guns and everytime [sic] we scored a direct hit, they set up such a roar of cheering that I couldn’t hear myself giving orders. We slapped right into them, then, and for good measure let go charges from our port and starboard thrower which exploded under him. By this time the Germans had had enough and lined themselves along the deck with their hands held high. They were all wearing their escape apparatus. As the Nazis plunged into the sea, the submarine weren’t up by the stern, shook for a second and took the last plunge. (Burrow & Beaudoin).

Whitby’s account on Stubbs notes G. N. Tucker’s memory of his CO during the battle. Tucker, who was on Assiniboine’s bridge during the engagement, saw first-hand how Stubbs handled the situation. He noted that it was “a masterpiece of tactical skill“ and despite there being a “deluged [of] machine gun bullets“, Assiniboine’s CO “never took his eye off the U-boat, and gave his orders as though he were talking to a friend at a garden party…” (navalmilitarymuesm)

Stubbs was made an Acting/Lieutenant-Commander nine days later in recognition of his actions (substantive May 1, 1943). Then, on December 3rd of that year, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order for his actions against U210, the citation noting:

Acting Lieutenant-Commander Stubbs’ decoration is awarded for gallantry, devotion to duty and distinguished service under fire. He showed outstanding kill, inspired leadership and conducted a brilliant action against an enemy U-boat. This officer, in the face of enemy fire at 0-300 yards’ range, and with the bridge structure on fire, handled his ship with dauntless resolution and courage, and pressed the attack with great determination to a successful conclusion. (London Gazette)

Stubbs left his ship and was posted ashore in October 1942, serving for a year as staff to the Flag Officer, Newfoundland Force. He didn’t appreciate working a desk – the sea was in his blood and he direly wanted another command. On November 6, 1943, his request was granted and he assumed command of the Tribal Class Destroyer Athabaskan. The vessel was considered an “unhappy ship” and the moment he stepped aboard he could feel that the crew’s morale “seemed to be at a low ebb.” (Burrow & Beaudoin). He noted gloomy faces – they didn’t smile, there was no laughter or “esprit de corps” among the sailors. The new CO walked through his ship, introducing himself to the crew and asking them questions. He wasn’t loud or arrogant, but rather relaxed and calm. Wit was one of his tools – he seemed to always find a way to cut tension with a well-placed joke.

Next, he called his officers into the wardroom for a meeting. Here he was a little more on point. Going over his observations, he stopped and looked each officer in the eye sitting around table.

“I can get along just fine without officers,” he stated, his soft voice in stark contrast to his steely stare, “but I need the men who will run the ship.” (Burrow & Beaudoin)

Stubbs allowed the meaning of his words to sink in – turn the ship around or I’ll find officers who can. Once they were dismissed, he then had a boatswain pipe “Clear lower decks” and instruct all presently not on duty to meet him there. He told the men to relax and stand easy before proceeding to chat with them about what he’d been noticing and having a heart-to-heart with his sailors. Again, he used some humour and soon the men were laughing and easing up. By the time he dismissed them, they were altogether different and feeling relaxed about the new captain.

In short order, the spirit aboard his ship was mended and Athabaskan began to run much like Assiniboine had. Officers and ratings gelled, saving the traditional naval pomp for when they were ashore and under the eyes of senior officers. At sea, they were first and foremost shipmates, and so long as everyone knew their roles and could efficiently perform their tasks, Stubbs didn’t mind being laxed on decorum and uniforms.

One example came-up the second evening of his new command. Stubbs had the quartermaster send a message to one of the officers – Sub-Lieutenant Annett –requesting a pair of dice with his approval. Annet proceeded to the junior ratings mess and quietly asked if any were available. The men, knowing that gambling wasn’t allowed in RCN vessels, were hesitant but, after some prying, a pair was found. Rather than confiscate them, Annet gave presented a chit, allowing them to have them. For the ratings, the gesture meant quite a bit.

On another occasion, an officer was ripping into some sailors for doing a poor job of chipping and painting the Tribal’s hull. His language was quite “salty” and Stubbs, seeing that the man was venting, calmly approached him and said, “Why don’t’ you don some coveralls and slide over the side so they can see firsthand how the job should be done.” (Burrow & Beaudoin) It wasn’t a suggestion and after a long bit of work – which officers didn’t do because of their seniority – the man learned his lesson while the crew had a good chuckle.

Stubbs considered himself a fair person and the crew soon grew fond of him. At the same time, they saw first-hand the command he had of the vessel, especially at sea. His experience showed and they knew the CO was a true sailor. They also sensed not to mistake his kindness for weakness – if they weren’t giving their best, he’d be on them in an instant. Stubbs could tolerate quite a bit, but not slacking in duties, especially those that could impact the safety of his ship. He was, after all, the person who had slugged-it out with a U-boat. They wanted to keep on his good side.

By November, Athabaskan was at sea doing some light escort work and by December 10, 1943, they were at Scapa Flow to commence artic patrols. They first escorted JW-55A to Kola Inlet. Aside from the days and night blending due to the diminished sun light and the frigid temperatures, nothing much happened for the first few days. However, on December 18th, the ship’s Huff-Duff operator intercepted a message at 1600hrs and immediately reported it to Stubbs (Burrow & Beaudoin). U-boats had spotted the convoy and were prepping to attack. The CO had no interest in waiting for that to happen. He ordered the helm to plot a course to where the submarine had been and readied a depth charge pattern. Athabaskan would straight-way make her presence and intent known – star shells fired over the area, the white streaks arching up into the late afternoon night and exploding, illuminating the area like the sun had suddenly appeared. Stubbs had his binoculars pressed to his eyes, leaning up against the bridge wall, and in the artificial light of burning magnesium, he noted the something jutting up from the waters at a 90 degree, like a dark grey rectangle.

His prey.

Water foamed as the U-boat, having now spotted the destroyer bearing down on them, began to submerge. It didn’t surprise the CO – he simply noted the position, raced ahead, and dropped depth charges. He didn’t wait long though, knowing other wolves would be in the area. He ordered his ship back to the convoy.

Assiniboine would be with her sister ship Haida when the 770-foot German Battleship, Scharnhorst, was ambushed (see DeWolf’s bio for more details). Throughout the encounter, Stubbs would routinely go onto the public address system: “Captain here men. This is a report of what’s going on there.” (Burrow & Beaudoin) He continued to relay details throughout the action until, at 1945hrs, he finally stated “Good news, men, Scharnhorst has been sunk! I guess we can stand down now and relax.” (Burrow & Beaudoin) Quietly, Stubbs was disappointed they didn’t get a chance to take part in the battle. He wanted to add another victory to his name but kept those thoughts to himself.

A few days passed and Athabaskan met up with HMS Ashanti. Both vessels were secured and Stubbs suggested to the other CO that they have a party in lieu of missing Christmas. The idea was well received and soon Canadian and British sailors “… roamed from ship to ship, exploring and visiting the several messes” while “Makeshift Christmas trees were put up in different places and simple gifts were exchanged.” (Burrow & Beaudoin) Stubbs had the junior-most sailor – Able Seaman John W. Fairchild – don the CO’s tunic and, as was tradition in the navy, the young man acted as the captain for the day.

Both ships turned south, joining several other destroyers and screening the battleship HMS King George V down to the Azores, where the crew enjoyed the warm weather and some much-needed shore leave. In February 1944, Athabaskan headed to Plymouth joined with the 10th Destroyer Flotilla for “Hostile” and “Tunnel” missions along the Normandy coast. On April 26, 1944, Stubbs would again have his chance to engage the enemy. The account is already described in detail on DeWolf’s CNTP bio – Stubbs proved adept at fighting enemy destroyers and his seamanship abilities aided greatly in the sinking of T29 along with Haida. He would received the Distinguished Service Cross for his part in the battle.

Things were about to take a tragic turn for Stubbs and his crew. Three days after their success, Athabaskan again accompanied Haida on another patrol and soon found themselves chasing down two enemy destroyers. Again, the details of that fateful evening are well accounted for in DeWolf’s bio. After both vessels began the attack on T27 and T24, both launched torpedoes in defence. Both ships expertly moved and avoided the attack, but at 0417hrs, Athabaskan’s good fortune ran-out. At the bridge, Stubbs looked up at some starshells which illuminated his ship. Enemy guns fired, salvos flying over them and ripping through some of Athabaskan’s rigging. That’s when Dunn Lantier, serving as the ship’s radar officer, received word that his operator had found two contacts off their starboard quarter, moving a very high speed. Based on the size, movement, and closeness of the vessels, he concluded they were E-boats. He was in the process of informing Stubbs when the ship was hit as she completed her turn.

The blow rocked the vessel, pushing her to the port and heeling her over slightly. Some on deck were knocked over by the kinetic force and, on the bridge, Stubbs and the rest of the crew flew into each other and onto the deck. Stubbs recovered quickly, pulling others up and immediately asking for damage reports. He already figured they’d been hit by a torpedo. X and Y guns were destroyed and a fire had started. The engines had also stopped.

“Torpedo hit near the gearing room,” came the first report. “Heavy damage aft the apron and Y gun collapsed. Steering gear out of action.” (Burrow & Beaudoin)

“Is the damage control party on the job?” Stubbs asked.

“After pump is gone sir,” came the reply, adding “the forward pump is being taken back and rigged now.”

“Try the after steering position,” Stubbs directed, “and better hoist out the seaboats, but don’t lower them yet. Haida is a making a smoke screen and will try to take us in tow later.” (Sclater)

He then ordered that Torpedo tubes be turned inwards and secured when Lantier requested permission to clear “B” gun of starshell. Stubbs gave the permission and the gun fired…

… for the last time.

Soon reports came that the ship was starting to settle in the water from her stern and Stubbs could see the writing on the wall.

“All hands stand by their abandon ship stations,” he directed. “Let Haida know.” (Sclater)

The bridge crew began to leave and one of the officer’s, noting a loose strap on one of the signalman’s lifejacket, said “Better keep that fast, son, you don’t want it to come off in the water.” (Sclater)

Stubbs stayed back, waiting for everyone to evacuate the bridge. Then, about ten minutes after they’d been struck, another blast exploded from the after part of the vessel. The ship listed and “great blobs of burning oil were falling everywhere, over the forward section of the maindeck and the bridge (Sclater). Stubbs began shouting for everyone to abandon ship, raising his arms to shelter himself from the flaming bits. There was no saving the ship now. In little time, those who survived were in the frigid waters, watching as their ship sank beneath the waves.

Despite his injury, Stubbs began to swim and check on his sailors, moving between Carley floats. He offered “words of encouragement to his men, urging them to sing and to keep their arms and legs in motion.” He ignored the stinging pain from his burns. His temperature was dropping and when some sailors on the float offered to trade places, he refused, saying he was fine, resting his burnt forearms on the side of the boat. At no time did his thoughts turn to his own safety – the lives of his crew were paramount.

When the raft came alongside Haida, he told the men to take the wounded first. He could have easily saved himself at this point, but that wasn’t Stubbs. He was every bit a naval officer and captain, and would remain so to his last breath. Realizing dawn was approaching and that they were within five miles of the coast, Stubbs yelled out “Get out of here Haida, get clear – E-boats!”

It was his final command.

Sometime late April or early May, several bodies from Athabaskan – sailors who had died from the explosion or succumbed to exposure – began to wash ashore along the coast of Finistere. Among a group of fifty-nine bodies was thirty-one year-old John Stubbs. A letter from the Naval Secretary to Stubbs’ widow confirmed that after his body was exhumed, dental records “correspond to those on file” and “that the body was clothed in a naval jacket with three stripes of gold lace for a Lieutenant Commander.” (service file letter dated June 21, 1944) His grave was located at the Plouescat Communal Cemetery, in plot 1, row ‘b’, grave number 35. He was awarded the DSO posthumously, the citation simply stating: “For Good Service in Action with Enemy Destroyers.”

128 Athabaskans perished and Canada lost, arguably, its most gifted captain.

DeWolf felt it too. After rescuing survivors, he wondered about the “young Johnny Stubbs” and, alone in his cabin, remembered “the youthful Stubbs as a popular lad, well known for his ability to beat any officer at the fast-moving game of squash.” (Burrow & Beaudoin)

Stubbs exemplary service should serve as a guide for future generations who make the choice to serve their nation at sea. He was a true champion, model leader, loving husband, caring commander, and loyal friend. His loss sent ripples through the RCN and, for Athabaskan’s survivors, Stubbs was foremost on their minds at reunions, their glasses held high in his honour. He would always be their captain and they, his sailors.

Indeed, Lantier’s words – simple yet poignant – put it best: “He would have gone straight to the top.”

Stubbs’ Awards and Decorations:

Distinguished Service Order (DSO), Distinguished Service Cross (DSC), 1939-45 Star, Atlantic Star, Defence Medal, Canadian Volunteer Service Medal and Clasp, 1939-45 War Medal.

A mountain was also named in his honour and is one of the eleven peaks along the multi-day Vancouver Island Trail.

Footnotes:

*Taken from an interview Ed Stewart did with Capt (N) Dunn Lantier and shared with the author. Ed was the founding president of the HMCS Athabaskan society and was instrumental in preserving the memory of the ship. He assisted Len Burrow and Emile Beaudoin in the publication of “Unlucky Lady: The Life & Death of HMCS Athabaskan 1940-44” and was well known to all survivors. Ed’s older brother “Bill” perished when the ship sank in 1944.

**His scores were as follows:

General/Modern History = 75

Lower Mathematics = 95

Physics = 61

General Knowledge = 87

English = 84

French = 60

*** Later to become Rear-Admiral Leonard Warren Murray, CB, CBE, RCN, the only Canadian to command an Allied theatre of operations during the war.

Sources:

Burrow Len & Emile Beaudoin. Unlucky Lady: The Life & Death of HMCS Athabaskan, 1940-1944. McClelland & Stewart Inc, 1982

Milner, Marc. North Atlantic Run. Penguin Books, 1990.

Sclater, William. Haida. Oxford University Press, 1947.

Lieutenant-Commander John Stubbs

https://www.blatherwick.net/documents/Royal%20Canadian%20Navy%20Citations/04%20-%20RCN%20List%20and%20Citation%20Korea.pdf

https://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/memorials/canadian-virtual-war-memorial/detail/2813902

A tale of two heroes

Prepared By:

Sean E. Livingston, Co-Founder CNTP and Author Oakville’s Flower: The History of HMCS Oakville