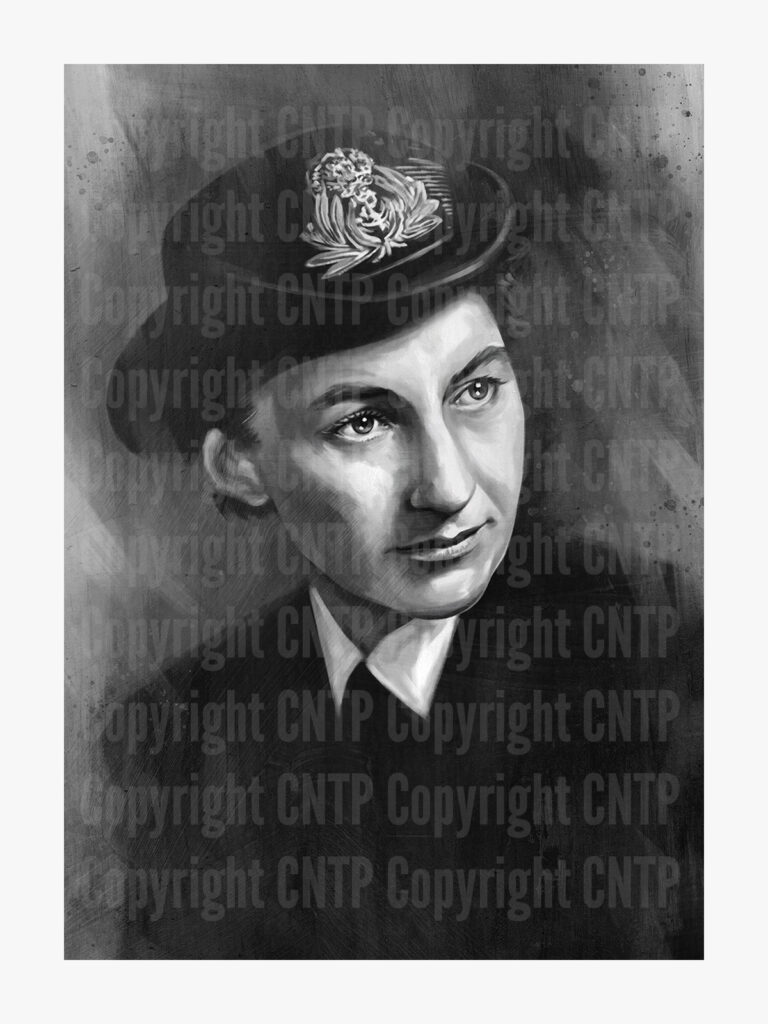

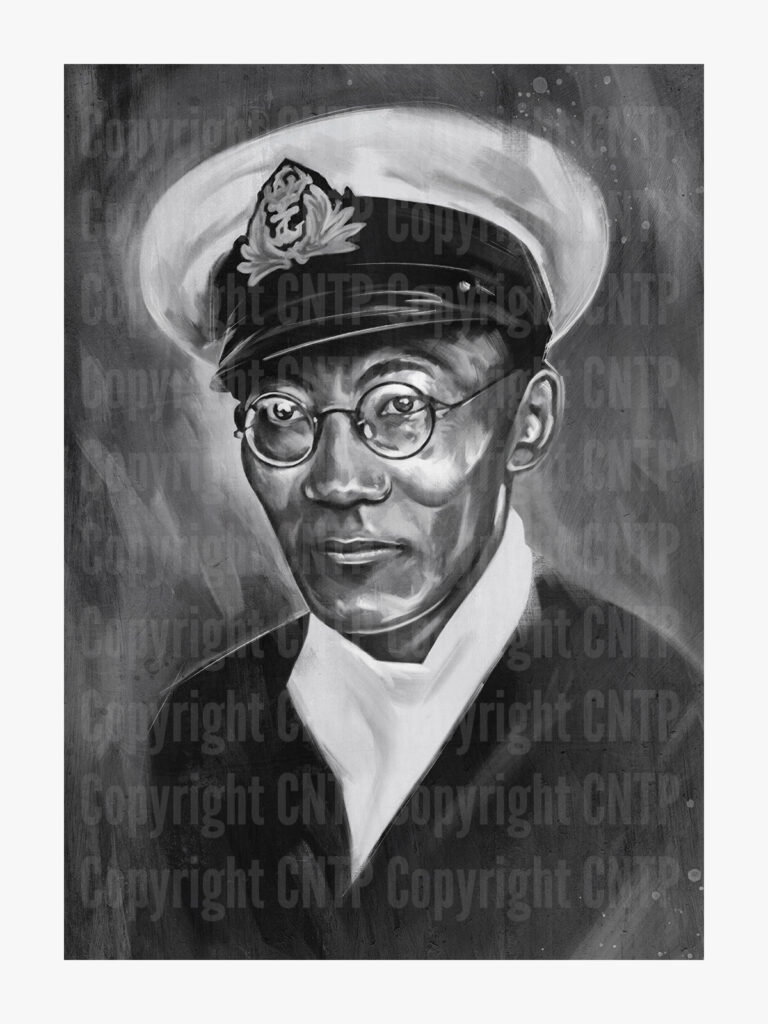

Lieutenant-Commander William (Bill) King Lowd “Lo” Lore RCN

“First Chinese Canadian RCN officer and first officer of Chinese descent to serve in any of the Royal Navies of the British Commonwealth”

By: Sean E. Livingston, CNTP Co-Founder and Author

Lore’s journey to the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) was far from typical. Born on February 28, 1909, in Victoria, British Columbia, he was a second-generation Chinese Canadian, his father a refuge who escaped Canton (Guangzhou) in 1885. From an early age, Lore proved academically inclined and motivated to learn. In 1929, he was accepted into McGill University to study mining engineering and moved across the country to pursue his post-secondary education. Unfortunately, at the same time he began his undergraduate studies, the American stock market crashed. Tuition and boarding costs rose, and the financial strain ultimately forced Lore to abandon his university schooling.

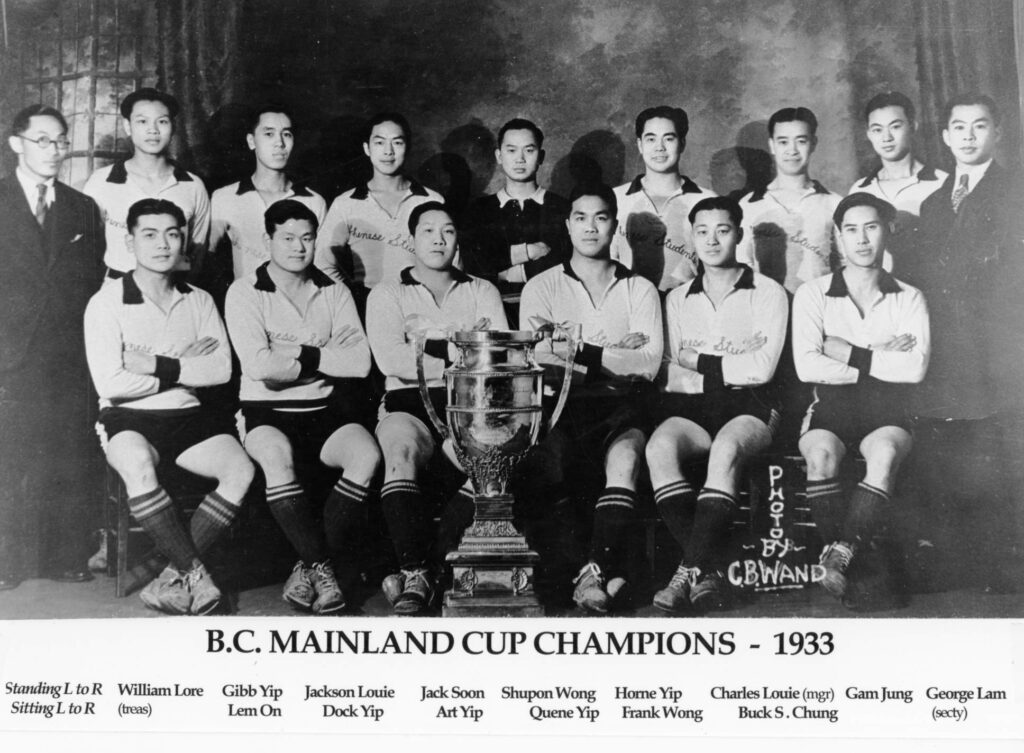

He returned home to Vancouver and took a job writing for a local Chinese-language newspaper. Lore became involved with the Chinese Students Soccer Team, serving as both club vice-president and treasurer. He helped make Canadian sports history when the team became the B.C. Mainland Cup Champions, defeating UBC Varsity at Con Jones Park on May 29, 1933 (B.C. Hall of Fame). By the end of the decade, Lore accepted a position with the civil service, becoming the first Chinese Canadian wireless operator of the Department of Transport, Radio Division, Marine and Air Service Branch. It wouldn’t be the last of “firsts” for Lore.

A quick learner, he took well to his new role – his supervisors were impressed with his attention to detail and technical expertise. Lore was on duty at Port Menier, Anticosti Island, when SS Athenia’s SOS “was intercepted and relayed to DOT, Ottawa, on 2/3 September 1939.” (Wong 60). A few weeks later, Lore received a call from the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) who were eager to recruit skilled wireless operators, especially those proficient in more than one language. Lore was keen to join but his prospects of wearing RCAF blue were soon dashed when the government announced that Canadians employed in roles deemed essential to the war effort were not permitted to enlist in the armed forces. Lore’s current job was among those “reserved” occupations.

Still, something within Lore had been kindled – he wanted to support the war effort and serve in uniform. Three times he attempted to join and each time he was rejected. Lore later explained, “I applied in 1940, ’41 and ’42, but they refused my applications,” adding, “I think they just saw on my application ‘Chinese’ and threw it in the waste basket.” (Manthorpe, Jonathan, Chinatown News, 5/3/94, Vol. 41, Issue 16) He wasn’t wrong. Not only had the government imposed restrictive and racist immigration policies, such as The Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 (Chinese Exclusion Act), which barred nearly all Chinese immigration into Canada for approximately 24 years, those restrictions also extended towards military recruiting throughout the commonwealth, specifically in the air force and navy (Wong 60). Although Lore wanted to serve his country, his country wasn’t interested – regulations were clear that “… a recruit must be a British subject and of the white race.” (Wong 60)

In December 1939, the department of transportation transferred Lore to the Air Services Branch at the St. Hubert airport in Montreal to help with the influx of aircraft being sent overseas in support of a besieged Britain. There he handled “radio range weather broadcasts and air ground radio voice communications” (Wong 60). In 1943, Lore transferred to Dorval Airport, serving as a radio electrician and shift supervisor working with Ferry Command and Direction Finding Station, tasked with locating German U-boats (Wong 60).

Finally, in March 1943, Order in Council PC 1986 “…removed all racial restrictions and specified only that the recruit must be a British subject” (Wong 60). As fate would have it, Lore came to the attention of none-other than Chief of Naval Staff (CNS), Vice-Admiral Percy F. Nelles, who urged the young man to join the navy. The CNS needed people with his skillset at Naval Service Headquarters (NSHQ) and personally vouched for his admission. Thus, for a fourth time, Lore stepped into a recruiting office and, after satisfying preliminary requirements, became the first Chinese Canadian to serve in the RCN. Lore likely didn’t realize the extent to which he’d just made history – upon accepting his commission he also became the first officer of Chinese descent to serve in any of the commonwealth’s navies. It’s important to appreciate the significance of this moment, as well as the long-term impact it would have on Canadian history: his joining the navy, and subsequent service during the war, would set an important precedent and assist marginalized groups to find future careers in Canada’s Armed Forces.

Lore first went to HMCS Montreal for some preliminary training and then attended HMCS Cornwallis for emergency officer training (Wong 61). By June, Lore had graduated from the RCN’s Officer Training Course, receiving a commission as a temporary Sub-Lieutenant, Special Branch. The next month, he was posted to Ottawa and began working at the Operational Intelligence Centre at NSHQ. There his previous experience at the Department of Transport proved invaluable – he took it upon himself to inspect equipment and instruct staff at “various Radio Interception Centres [sic]” (Wong 61). By October, Lore had been made Officer in Charge of the Naval Radio Interception Centre at Gordon Head, Victoria, and then, in December, became the RCN’s liaison officer to the US 13th Naval District’s radio intelligence establishment, a post he held until May 1944 (Wong 61).

He returned to NSHQ and began working with the newly formed Combined Services Radio Intelligence Unit and was promoted to Lieutenant (SB) RCN. Then, in September 1944, he was put on loan to the RN and went overseas aboard the unescorted, fast troopship Andes, to train in advanced high frequency/direction finding at HMS Mercury (Wong 61). However, once the ship arrived in Liverpool, concern over Lore’s ethnicity arose when a British Major, who had come aboard to inspect the troops, told him that he “would not be allowed to land because [he] was Chinese and did not have a visa.” (Wong 61) Other officers vouched for Lore – after all, only citizens could join the service and Lore possessed proper military identification. After some back-and-forth, he was finally allowed ashore and reported to his post in London (Wong 61).

Although his character and skills were impressive, it was Lore’s ability to communicate beyond the English language that set him apart. After a brief assessment, Lore found himself selected to join a two-man team at the Combined Services Detailed Intelligence Corps in Burma. He found the whole situation confusing. As he later explained, after reading and interpreting “two lines of a Chinese epigram on screen… [I] suddenly became a Japanese intelligence officer.” (Wong 61) And so Lore found himself again on ship, this time heading to Southeast Asia Command to serve under Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten. In January 1945, he arrived at Colombo, Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka), and reported to HMS Lanka (Wong 62). He then travelled deep into the jungle to a top-secret RN transit camp, HMS Mayina, where he played an instrumental role in the development of a large, joint amphibious and air attack on Japanese forces in Rangoon, Burma (present-day Myanmar). Code named Operation Dracula, the plan saw British and Anglo-Indian forces successfully liberate the city, contending with limited Japanese opposition, mostly in the form of snipers. By May of 1945, the enemy had been fully expelled.

With news that fighting in Europe had ended, Lore was dispatched to the British Pacific Fleet and then subsequently seconded to the American 7th fleet to serve with G-2 (American Intelligence) Allied Command Headquarters near Brisbane, Queensland (Wong 62). After the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Japanese government began to negotiate terms to surrender. Lore was sent back to the British fleet and reported to Admiral Sir Cecil Harcourt aboard HMS Venerable, to serve as “the Admiral’s Lieutenant.” (Wong 62) Lore had little understanding of what this new role would entail. The Admiral’s secretary, Commander Trythall, explained it to him: he would be “the Admiral’s eyes, ears, and legs and was supposed to be at the Admiral’s side at all times possible AND be able to answer any query put to him.” (Wong 62) It was even suggested that Lore “study up all references to Japanese naval vessels in Jane’s Fighting Ships.” (Wong 62)

Lore took the advice to heart and engrossed himself in everything he could find that had anything to do with the Japanese fleet. It was like preparing for an ambush, except the threat was a knowledge-based test which could be administered at any moment. Fortunately, Lore had a mind for facts and figures, and spent his spare moments reading and taking diligent notes. He accompanied Harcourt to HMS Indomitable, a fleet carrier, and by late August, orders came from Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser to occupy Hong Kong Island and Kowloon, leaving the New Territories for the Chinese to liberate (Wong 64). It was here that Lore’s studies proved invaluable. On August 28th, a Hellcat Patrol reported that it had spotted a flotilla of “30-odd speed boats in formation travelling in the direction of the Fleet” (Wong 64) and that they would be on Harcourt’s forces by that evening. The Admiral turned to his aide and asked him to identify the vessels.

At last, the test was sprung.

Thankfully, Lore already had the answer and wasn’t left standing there dumbfounded or scrambling. The whole time, he’d been quietly reviewing the reports and, based on his knowledge of Japanese ships and tactics, which at this point was quite extensive, he concluded they were “suicide boats” (Wong 64). Upon hearing Lore’s confirmation, Harcourt ordered the threat be neutralized and sent a force to intercept and eliminate the vessels. The moment was another feather in the young Lieutenant’s cap – the Admiral was impressed by the speed and accuracy of his identification and the incident would, in part, influence his decision to task Lore with a special mission.

On August 30, 1945, Lore found himself aboard HMS Swiftsure, one of three minotaur-class light cruisers built for the RN. It was dawn and he was in the Admiral’s bridge, looking out to the horizon as the ship led “the Fleet heading towards Hong Kong at median speed all ships companies in ‘Ready Action Station’ status.” By 0900hrs Swiftsure was already in Hong Kong waters and joined two ships from the Royal Australian 21st Minesweeper Squadron, who proceeded to escort the cruiser towards Victoria Harbour. Lore noted the exact time they entered in his diary – 0930hrs – and added that “… the harbour was absolutely cleared of shipping of any kind – not even a Junk or sampan!” Things weren’t any livelier ashore. He observed that “there [was] not a single living person seen on the whole visible waterfronts on Hong Kong Island or on Kowloon side!” The Japanese had set strict curfews and the locals had learned, through brutal punishment, not to disobey the invader’s rules. Interesting to note, Swiftsure was the first allied ship to enter Victoria harbour since Hong Kong’s capture back in December 1941.

At 0945, Swiftsure arrived at the RN’s shore base, HMS Tamar. Originally a ship depot, the 3,650-ton troopship was scuttled during the island’s failed defence to prevent it falling under Japanese control. Now, all that remained was the dockyard and associated buildings. Harcourt was aware of Canada’s courageous defence of Hong Kong and directed his aide to lead the 1st platoon of Royal Marines to secure the area, explicitly instructing him to “make sure [he] would be the ‘FIRST BRITISH OFFICER’ ashore and to stand guard at the Main Gate of ‘Tamar’ until relieved.” Before leaving, Lore drew a service revolver and some extra ammunition from the ship’s vault, checking the pistol before placing it into a holster affixed to his belt. He then met his contingent of marines, briefed them about their mission, and led them off the ship.

As he walked onto the base’s main roadway, he paused and glanced around. Just like the rest of the shoreline, things were quiet and void of any activity. Something didn’t feel right. After a moment’s reflection, Lore finally realized what it was – there were absolutely zero sounds. Dense urban centers were always plagued by noise pollution – traffic, horns, music, construction, and throngs of commuters – but here the persistent city ‘buzz’ was missing. And that alone was enough to tickle the hairs on the back of his neck. The marine next to him tightened his grip on his rifle and raised it ever so slightly. Lore figured he wasn’t the only one feeling wary of their surroundings.

Carefully, he led them up the road, the marines fanning out to clear buildings and adjoining passages as they went. Safety was paramount and despite reports that the enemy had vacated the area it was better to be cautious, lest they unwittingly trigger a boobytrap or walk headlong into an ambush. If half of what he’d heard about the Japanese was true, they would be wise to remain vigilant. Lore’s senses were on high alert and although he wasn’t holding his pistol, his hand lingered close to the grip, ready to draw and use his weapon if need be.

Before coming ashore, he’d taken a few moments to study a map of the base. Although outdated, he presumed the general layout would still be the same. The road they were presently on, which was wide enough to accommodate two transport trucks travelling side-by-side, should, if he’d read the map correctly, lead them to their objective. Just then it dawned on Lore that he was standing in the middle of the thoroughfare in his crisp, tropical whites. As resplendent as they were, the marines’ muted combat dress was clearly better suited for this sort of work. He might as well be holding a large, illuminated sign reading ‘OFFICER’ – a sniper couldn’t resist such an obvious target. Feeling exposed, Lore moved to the side of the road, hoping the buildings would grant him some cover.

A marine came up and reported that one of the buildings contained an “enormous” amount of Japanese currency. Lore, grateful for the distraction from his anxious thoughts, followed the soldier into the structure. He performed a quick survey, noting tables, chairs, filing cabinets, and office supplies – everything one would expect in an administration workspace. What didn’t belong were the stacks of yens in the back corner, rising from the floor in neat piles. They reached as high as his waist and Lore couldn’t help but let out a whistle as his mind tried to calculate just how much money he was looking at. He’d never seen so many bills in one place.

“Did anyone touch them?” he asked.

“No sir,” a marine replied, “I called for you straight away.”

Lore nodded. “Leave it be, I’ll report it when we get back to the ship. Let the Admiral handle it. Last thing any of us need is to be accused of plunder.”

They exited the building and continued their sweep, eventually arriving at their objective – the main entrance leading out to the Kingsway. Lore followed Harcourt’s orders to the letter, opening the heavy gate and stepping out onto the pavement beyond. His men took-up positions around him.

At 1330hrs, Lore received a visit from Lieutenant John Gunyan, a fellow Canadian serving aboard Swiftsure. Harcourt wanted both men to conduct a “foot patrol of the business district” and Gunyan, fluent in Japanese, was an obvious choice. The fact that the second RN officer to come ashore was also Canadian made Lore beam with pride, a point he would later note in his diary. Both men proceeded on their journey, leaving the marines to stand sentry at the gate. By this time Lore was feeling better about the area, his hours at Tamar’s entrance – all uneventful – leading him to conclude that Japanese forces had indeed withdrawn from the surrounding area. He doubted they would face any opposition this close to the base, especially with a flotilla just off the coast. As they patrolled, they finally came across some locals who had ventured from their dwellings to do some shopping. The presence of uniformed RN officers both surprised and relieved the citizens, and Lore noted that they acted much like prisoners, afraid to even make eye-contact. He wondered if their mannerisms hinted at the difficulties the population had endured under years of Japanese occupation. An hour into their reconnaissance, Lore and Gunyan met their “first Hong Kong European” who, upon recognizing their uniforms, began to cry.

“I’ve waited almost four years to see this,” he said to them.

The man, who had been a police officer before the invasion, would eventually become a friend of Lore’s and later re-join the force and serve as Superintendent of the Special Branch. By the time they completed their patrol, Lore had grown concerned about what he’d witness and heard. He no longer doubted that what he’d been told about the Japanese and their ill treatment of civilians was indeed true.

Both men returned to Swiftsure around 1700hrs, and Lore gave a verbal report to Harcourt. He relayed that shop owners were already beginning to resume business and pedestrian foot-traffic had grown. He then had some supper before going back ashore – again armed with a pistol – to sweep “the darken streets, alleys and lanes on the hillside… from Hollywood Road to Queen’s Road.” Accompanied by some Royal Marines, he noticed what appeared to be looters nosing about some shops in the distance, but most fled upon hearing their approaching footsteps. As for the others, his marine escort scared them off by firing a few rounds into the night. Their patrol was quite successful – the next morning Lore reported none of the shop owners had anything stolen (although there were multiple attempted thefts).

At around 0130hrs, Lore made it back to Swiftsure’s motorboat. The Coxswain looked relieved to see him, noting that the crew had heard gunshots and were concerned for his welfare. When he reached the ship, he was thankful that Harcourt had already retired for the night. He was tired from being on his feet all day and direly needed rest. Lore went straight to his cabin, kicked off his shoes, and flopped onto his bed. He didn’t even remember falling asleep.

On August 31, a somewhat rested Lore awoke and began his usual morning routine: he washed-up, dressed into a fresh set of naval whites, and ate a decent breakfast before reporting to Harcourt’s cabin for 0930hrs. Outside the entrance, Lore noted “a young British Sub/Lieutenant [sic] and a grizzled old C.P.O.” standing about. Acknowledging them both with a nod, Lore entered, paid his compliment, and removed his hat before proceeding to report on the previous evening’s events. After concluding, Harcourt leaned forward, planted his forearms onto the wooden desk, and looked Lore in the eyes. Something important was on his mind.

“Lore, you must have heard about the POW’s after the surrender of Hong Kong in December, 1941?”

“Aye, sir.” Lore replied.

“Well, those POW’s, including Canadians, British and Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps, had suffered Japanese tortures, forced labour and mal-treatments for about four years,” Harcourt explained. “Those still surviving are in dire straits requiring immediate relief.”

The Admiral sighed. “However, we have no idea where the camp is situated, no street maps or intelligence reports. Further, by agreement with the Japanese, all of Kowloon will be in the full armed control of the Japanese and we cannot afford the time to go through the protocol of formal negotiations before we attempt to open-up the camp for reliefs to be brought to the POWs.”

Lore nodded in agreement.

“So, we must somehow effect the opening-up of the camp as soon as possible by any means possible.” Harcourt pointed a bony index finger at Lore before concluding, “In other words, this difficult mission is left for you.” He then shifted his finger and gestured to the hatchway, to where the young officer and chief awaited. “There’s your army, both volunteers. A Japanese-speaking officer and one tough CPO!” (Manthorpe)

“Aye sir, but if I may…”

Harcout cut him off, “I leave everything to you and you have my permission to use your discretion and ingenuity, but try not provoke the Japanese sentries or camp guards.”

“Understood sir,” Lore answered.

“Good man,” the Admiral said with an approving smile. “Now, go and open up the camp – relief will be sent the moment you indicate that it’s open.”

Lore replaced his headdress, saluted, and turned about to exit the cabin.

“Oh, and Lieutenant?”

Lore stopped and glanced back at Harcourt.

“Good luck!”

“Aye sir, I’ll try my best,” he promised.

Lore left the Admiral’s cabin, introduced himself to the two men waiting outside, and then found a spot to brief them on their mission – ‘brief’ being the optimal word as he didn’t have much to share. They’d been assigned an extremely difficult task with little guidance on how to accomplish the objective. Lore didn’t even know where to start his search. He’d never been to the mainland and without any intelligence reports or concrete information, he was moving in the dark. Making matters worse, they didn’t even have resources at their disposal – no aircraft or vehicles. That meant they’d be on foot, searching an area approximately 400 square miles in size. If they went in the wrong direction, they could search the better part of the day and be nowhere near the POW camp. And Lore had to accomplish his mission before nightfall.

Finding the camp was only the first obstacle. Getting into the camp was the real trick. Lore had to somehow convince the guards to allow them access and not get shot in the process. Japanese soldiers had a reputation for many things, but patience and negotiation weren’t among them. If their orders were to bar anyone from entering the camp, they wouldn’t hesitate to use lethal force.

Before debarking, they armed themselves with .38 revolvers – relatively inconspicuous and reliable – and filled their pockets with extra ammunition. They then proceeded to Swiftsure’s cutter, which was already alongside and ready to depart.

“Another jaunt ashore, sir?” the coxswain teased as Lore lowered himself into the boat. It was the same man who’d ferried him across the channel the other day.

“Didn’t get to finish my sightseeing,” Lore joked.

Lines were cast and the vessel slipped into the channel, heading in the direction of the mainland. Lore thought for a moment and then tapped the coxswain on the shoulder.

“Take us to Flagstaff Steps,” he ordered, and the cutter immediately turned about, heading south towards HMS Tamar. Both the sub-lieutenant and chief shot him a questioning look.

“I thought of something that might help us,” he explained, adding “I also think its better if we sneak ashore. We’ll probably be spotted in the cutter.” He gestured to the small white ensign at the stern, flapping in the wind. The Japanese were likely watching, and the last thing Lore wanted was to be intercepted by an enemy patrol upon making landfall. It would undoubtedly lead to questions and if someone warned the camp about their mission, the prisoners might be moved to another location. Lore knew he was being overly cautious – it was unlikely such a thing would happen, especially after Hirohito announced the country’s surrender and acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration – but he worried that some commander might view the POWs as a bargaining chip.

The cutter came to their destination and in short order, the three men were left ashore, watching the vessel as it proceeded back to the ship. They were standing at the far end of Flagstaff’s front lawn, a large white building that, at first glance, appeared to be the residence of some wealthy person. Lore noticed it the other day – how could he miss it? Unlike everything else, this was clearly European in design; two stories with rows of smooth columns lining the entire front and sides of the building. It was a commanding structure, situated on a spacious piece of lakeside property, replete with trees and gardens. But what really caught Lore’s attention was the state of the lawn – it was still in decent shape, which meant the building had been occupied even after the invasion. A bit of research indicated that, prior to 1941, Flagstaff had served as the residence and headquarters of the Commander of British Forces in Hong Kong. It seemed the Japanese had also used it as a command center. If Flagstaff had been evacuated as hastily as the rest of Tamar, there was a chance they might discover a trove of intelligence in the building, including the location of the POW camp.

They proceeded up to the front entrance. The building appeared unoccupied and when the chief tried the main door, he found it unlocked. Lore wasn’t taking chances – he and his team carefully swept the building and cleared each room before starting their search. Several rooms had been converted to administrative offices, each containing walls of cabinets, folders, and lots of paperwork, but that didn’t interest Lore. What he wanted was a map, the sort usually found in an HQ – large scale print with markers pinpointing key locations. Unfortunately, if there was one, the Japanese had removed it before evacuating the building.

Lore considered the situation. The sub-lieutenant was the only person who could read Japanese and he didn’t fancy waiting around while one officer waded through hundreds of files. They simply didn’t have the time. So, he made the decision to leave – perhaps they could find a local on the mainland who could point them in the right direction. Close by, ferries were in full operation, moving locals to and from the mainland. It would be easy enough to blend-in with the rest of the commuters.

They left Flagstaff and headed to the terminal, boarding the ferry on route to Tsimshatsui. Nobody else was in the vessel, save for the crew (they didn’t know anything about the POW camp). The locals were wary about crossing the channel – the Japanese still had control over the other half of Hong Kong. So, the trip to the mainland was quiet. Lore kept his eyes glued to the shoreline, hoping to see people going about their day, but as the vessel neared its destination, he failed to spot a single “living soul at the Ferry Concourse”. The area seemed void of any activity except vessels berthing and slipping from their respective docks.

“So much for that idea,” he thought.

Once ashore, Lore was yet again forced to update his plan. They needed to find someone who could tell them where the camp was but the area surrounding the terminal was empty. Even across the street, not one pedestrian or vehicle could be seen. It was a city in transition – the Japanese had surrendered but hadn’t left and until the invaders were expelled, nobody was leaving their homes.

At last, Lore made up his mind. They would split up: the sub-lieutenant and chief would head into the city in search of a Japanese sentry while he would sweep along at the shoreline. They would all meet up again at the concourse in half an hour. Before they parted ways, Lore explained that the subaltern (the CPO couldn’t speak Japanese) wasn’t to divulge the nature of their mission and was to ‘encourage’ the soldier to reveal the camp’s location. Hopefully, the guy would be the talkative sort and unwittingly give up the site.

Fifteen minutes passed. Lore strolled around the area but came across nobody on the streets and pathways. He began to regret his decision to stay behind when suddenly the sound of an engine caught his ear. A black limousine came down the road and pulled up to the curb in front of the ferry concourse. He quickly approached, intent of questioning the driver when, to his surprise, doors opened and his companions exited.

“You found a car?” he questioned, looking gob smacked. He then realized that neither of them had driven. Instead, a Japanese man was at the wheel. The sub-lieutenant explained everything that had occurred: both men had ventured into the city but, like Lore, hadn’t come across anyone. About ten minutes into their search they noticed the Peninsular Hotel and figured it was a good place to find someone. Their timing couldn’t have been better – upon entering, they bumped into a Japanese Police Chief. After some conversation, the man not only gave them the information they needed, but even offered to have his driver take them to the Sham Shui Po prison camp.

With renewed vigor, Lore entered the vehicle and took a seat behind the driver. The car took off and made for the city outskirts. According to their guide, the camp wasn’t more than fifteen minutes away, which was welcome news. If all went well the POWs could be liberated before noon. City buildings became factories as they passed into an industrial area. Some appeared to be in operation – Lore noted the odd truck hauling raw materials. Still, things were disturbingly quiet, but he figured that would all change within a week.

The car slowed to a stop and Lore leaned to see past the driver, noticing a tall fence and gate. The road had taken them right to the prison’s entrance. He checked his watch and noted the time: 1040hrs. Six Japanese soldiers stood guard with rifles in hand.

Lore turned to the sub-lieutenant. “Would you mind asking our chauffer if he could mildly request for the guards to open the gate for us to drive into the camp?” He didn’t know how the soldiers would react but hoped they wouldn’t make things difficult. Lowering his window, the driver relayed the message, but the guard’s simply laughed and gestured for them to leave. The driver turned back and spoke to the sub-lieutenant.

“He says they told him to leave,” the officer explained.

“I caught that,” Lore thought, and then replied, “We’re getting into that camp. Tell the driver to explain to them that we are British Naval Officers under direct orders from the Commander-in-Chief of the British Liberation Fleet. The camp is to be opened and reliefs brought to the POWs.”

Again, the driver spoke but this time the guards didn’t laugh. Instead, they chose a more direct form of communication – raising their rifles.

This wasn’t playing out how Lore wanted, but the show of force didn’t intimidate him. Instead, he felt his temper flare at the guard’s stubbornness. Were they clueless? The emperor had announced Japan’s surrender, a flotilla of allied warships was in the channel, and these men were less than a day away from becoming prisoners themselves. There was nothing to gain by barring their entrance to the camp. Lore decided it was time to ditch the diplomatic approach in favour of something more assertive.

The driver turned back, the look on his face asking, “what now?”, but Lore was too busy examining the gate to respond. It was only barred by a single plank of wood. If the vehicle were to drive into the entrance, they could easily break through. He looked at sub-lieutenant and said, “I want the driver to back-up the car about five meters.”

Slowly, the car crept back and stopped. The guards looked on with a mix of confusion and interest. Lore then ordered the sub-lieutenant and chief to point their revolvers out their respective windows. The driver was to slowly bring the car to the gate – he was not to stop, even if the guards refused to move – so that the front end was basically touching the entrance. The chauffeur hesitated and asked the sub-lieutenant to repeat the instructions, but Lore interrupted.

“Move forward,” he commanded, adding emphasis on the latter word.

The windows were lowered, arms extending out holding pistols as the car crept forward. This time Lore loudly instructed his subaltern to have the driver “tell those so and so guards that I give them exactly five minutes to open the gate or we shall shoot our way through!”

It was a bold and dangerous move. Lore had no idea how many soldiers were behind the wall (there were in fact thirty) and if things escalated, they likely wouldn’t survive the fight. The sentries were clearly taken by surprise. Rather than shoot, they hesitated and looked to one another. This wasn’t something they were prepared for – whatever instruction they’d been given, Lore guessed it was only to deter the enemy from entering the camp, not physically prevent it. In the absence of any clear direction, the guards shuffled out of the way and watched as the vehicle’s bumper came within an inch of the gate. The stalemate was eventually broken when one of the soldiers darted off. At first Lore wondered if he’d simply cracked under the stress.

“No,” he told himself. “He’s going to ask someone what to do.” Hopefully the person in charge had more sense than his men, otherwise things were about to get dicey. The guards were hardened soldiers and wouldn’t hesitate to attack if ordered to.

The minutes passed slowly, and Lore could hear his own heart beating. He held his revolver with a rock-steady grip, finger resting on the trigger. He stole a glance at his wristwatch – they were approaching the five-minute mark. In a matter of seconds, they would open fire…

Thankfully, as the hands of his clock neared zero hour, the guard suddenly returned and began speaking urgently to the other men. They immediately lowered their weapons, removed the board, and opened the door for the vehicle to pass. Lore also ordered his men to stand-down.

The bluff had worked.

The camp was a converted military barracks, located on a large plot of land situated along the harbourfront. They first passed some lager buildings, which Lore assumed housed the guards, before stopping at an intersection at the center of the compound. To the left, closest to the water, were buildings that Lore understood housed prisoners who were officers. To his right, columns of basic single-story structures stretched into the distance, organized into neat columns consisting of rows of about six buildings, separated by a main dirt road. The entire camp was surrounded by a large fence with sentry towers stationed at each corner. Lore and the others exited the vehicle and glanced around. Nobody was outside. Large mountains loomed in the distance, a natural barrier to the rest of the mainland. Lore figured the prisoners were likely inside, seeking relief from the rising heat, and proceeded to the closest building on his left. He knew that Canadian and British officers were housed in separate, adjacent barracks, and directed the sub-lieutenant to the appropriate structure, while the chief stood guard outside.

Lore entered the dimly lit barracks and nearly recoiled from the stench of sweat and filth. There were ten men sitting at a crude wooden table, all shirtless and dangerously gaunt. They looked more akin to skeletons than people – he would later report “You could see their bones through their skin.” They froze, surprised by the sudden appearance of somebody wearing clean, tropical whites. Lore broke the tension.

“I’m a Canadian Naval Officer and I’m here to liberate you guys,” he announced, adding with a smile, “Aren’t you glad to see me?”

The men blinked, momentarily confused before connecting the dots. They bolted from their seats and rushed forward to greet their liberator, wrapping thin arms around Lore and shouting in joy. More came from the upper rafters, descending ladders and joining the throng until thirty men surrounded him. They thanked him, asked him questions, and even took interest in his cap badge.

“You’re the first Canadian we’ve seen for almost four years,” one said.

“How we’ve waited for this day!” another exclaimed.

The men began to cry, tears flowing freely from their eyes. They shared stories of their ill-treatment and suffering and soon Lore began to weep with them.

“I had neve seen so many men in tears together,” he later reported. “But they were happy tears! […] they were like skeletons and I realized that the young happy-go-lucky ‘boys’ of less than 4 years ago had became old men because of the maltreatments they had suffered, causing many fatalities among them.”

The soldiers soon dug up an old Union Jack they’d hidden from the Japanese. Lore ordered the head guard to “sink the Rising Sun” and hoist the other flag into the air. It stood tall above the camp and soon other POWs, hearing the commotion, gathered around, eyes watering at the sight of the flag and their liberators. Lore assured the men that medical supplies were on the way and that they would get “clam chowder” aboard Swiftsure. The crowd cheered in response. In the distance, guards looked on glumly and lit cigarettes to calm their nerves. They knew it was the end.

That afternoon, Lore gave his report to Harcourt who was pleased by the outcome. The Admiral commended them for their actions and ordered additional medical aid and men be sent immediately to the camp. Lore would later reflect on the incident, saying “I was quite satisfied that we had completed the difficult mission and remembering my meeting with the Canadian Officers, I considered our dangerous mission worthwhile.”

That evening, he retired early to bed. He’d certainly earned a good night’s rest.

Lore remained at Hong Kong with Harcourt, not only continuing as the Admiral’s staff Lieutenant but also serving with the Naval Intelligence Unit, the Joint Intelligence Unit, and acting as liaison officer to China. Despite numerous sources stating that he was present for the official surrender of Japanese forces in Hong Kong on September 16th, his own account states otherwise. Instead, he was aboard ship, “glued to the radio broadcast from Hong Kong of the official singing of the surrender of the Japanese Garrison in Hong Kong and the Ceremonial Parade afterwards.” Lore wished he was there, noting that he and his fellow officers, “were sorry to miss the ceremonies, especially I, who would have been standing by Admiral Harcourt’s side at the signing of the Surrender and at the parade afterwards.”

Despite the war being over in the Pacific, Lore stayed on loan to the British Navy until November 1946 and then returned home, where he was promoted to Lieutenant-Commander. During the Korean War and communist expansion throughout parts of Asia, Lore served in Hong Kong doing intelligence work throughout the southeast. The details of his work remain a mystery – Lore was “still reluctant to talk about [it]” during an interview in 1994. In 1957, he left Canada and settled in Hong Kong, becoming an insurance agent. Then, at the age of 51, Lore earned a law degree at Oxford University. He opened his practice in 1962, not far from HMS Tamar. In 1994, Governor General Ray Hnatyshyn presented him with a military, long-service certificate. He died on September 22, 2012, having lived to the impressive age of 103.

On October 5th, then Minister of National Defence, The Honourable Peter MacKay, expressed his condolences on the passing of Lore and gave the following statement:

“Mr. William Lore’s drive and determination to serve his country and to achieve recognition of Chinese Canadian as full members of Canadian society serve as a wonderful example to all of us and show that we all can make a difference. As a sailor, Lieutenant-Commander Lore made Canada Proud.”

Lores’ Awards and Decorations:

1939-1945 Star; Burma Star with Pacific Bar; CVSM & Clasp; and 1939/45 War Medal

Sources:

Wong, M. The Dragon and the Maple Leaf: Chinese Canadians in World War II. Pirie Publishing, 1994.

Manthorpe, Jonathan, Chinatown News, 5/3/94, Vol. 41, Issue 16

https://www.royalmarineshistory.com/post/liberation-of-rangoon-operation-dracula

Prepared By:

Sean E. Livingston, Co-Founder CNTP and Author Oakville’s Flower: The History of HMCS Oakville

Special thanks to Robert Yip (Lore was his 2nd Uncle) for his on-going assistance.