“Hard-Over Harry: Legendary Ship Captain and Canada’s Nelson”

The fact that most Canadians aren’t familiar with DeWolf’s name is truly baffling. One of the most effective and battle-hardened ship captains of any allied nation during the Second World War, the total number of enemy vessels sunk and/or damaged under his command rivals, and even surpasses, many of other allied nations. And he did so in a distinctively Canadian fashion.

Harry George DeWolf* was born in Bedford, Nova Scotia on June 26, 1903. Throughout his childhood, he was exposed to ships and maritime affairs – his father, Henry G. DeWolf, was the owner of a ship brokerage, DeWolf & Sons. He spent the summers sailing along the shores of Bedford Basin and dreamed of one day traveling the world’s oceans and seas. And when the Great War erupted, DeWolf grew eager to join the navy, resenting being too young for a commission. When he turned 15, he applied to the Royal Naval College of Canada (RNCC), which accepted applicants between the ages of 14-16 and prepared them for a career as a naval officer. In September 1918, Cadet DeWolf travelled to the west coast to begin his formal education in naval sciences (the school had recently been relocated to British Columbia after the original building was damaged by the Halifax Explosion)** but by this time the war was already coming to an end. That November an armistice was signed, ceasing all hostilities and, along with it, DeWolf’s opportunity to participate. While disappointed – even after four years and a multitude of casualties, many youths were saddened to have been sidelined – the characteristically calm and quiet DeWolf shrugged it off and turned his attention to his studies.

Over the next three years, DeWolf developed a foundation of knowledge in naval history, science, engineering, navigation, mathematics, and languages. His education also included a great deal of physical exercise, drill, and leadership training. DeWolf, a sharp-witted and determined youth, did well in the program and upon graduating was made a Midshipman in the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN). He was briefly appointed to the shore establishment HMCS Naden, formerly a wooden schooner used by the college to train officers in basic seamanship, before packing his kit and heading overseas to train directly with the British. In October 1921, he reported to the Royal Navy (RN) and was subsequently posted to his first warship: HMS Resolution. While DeWolf technically served in HMCS Rainbow during the first year of his education, at that time the retired cruiser served as a depot ship – a convenient place for the RNCC to house their students until appropriate accommodations could be made ashore. Now DeWolf would work aboard an active ship, and the 620ft Sovereign-Class (aka Revenge-Class) Battleship, one of five in service with the RN, with its four 15-inch twin-gun turrets, was the sort he’d dreamt about.

DeWolf was amassing a wealth of experience aboard a range of vessels, which he hoped would increase his prospects of command. However, something troubled him – a nagging issue that continued to plague him since first going to sea. In all this time, DeWolf had yet to develop his sea legs. He’d been told to give it time, that his body would eventually adjust, but that was eight years ago. Now, the truth couldn’t be ignored – he would never adapt to the motion of a ship. Most people would resign themselves to fate and accept the reality that they weren’t cut-out for a naval career.

Not DeWolf.

Although being at sea greatly affected his appetite and left him generally uncomfortable, he wouldn’t give up. So, he forced himself to live with it, even sleeping in uniform while sitting-up in his bunk to avoid becoming sick to his stomach (Green). For those who have ever been seasick, it’s easy to marvel at DeWolf’s ability to take this “in stride”. The man possessed an iron resolve.

Over the next few years, DeWolf moved between various ships and postings on both of Canada’s coasts: HMC Ships Champlain, Naden, Stadacona, and then his first command as CO of the 130ft Battle Trawler HMCS Festubert from April 1930 to July 1932. Next, DeWolf became First Lieutenant – i.e. Executive Officer (XO) – on destroyers Vancouver in 1932 and Skeena the following year. With two successful postings as XO, DeWolf rose to the rank of Lieutenant-Commander and moved to headquarters in Ottawa as the new Assistant Director of Intelligence and Plans. By 1936, he was sent again overseas to work with the RN as a staff officer and was in England when the country declared war on Nazi Germany. By October 1939, DeWolf returned home, appointed CO of the C-Class Destroyer HMCS St. Laurent, known to all sailors in the fleet as “The Old Sally Rand”.

Although excited about the command, his age concerned him. Nearing thirty-eight – far older than other captains – he suspected he’d soon be transferred to a desk job and that St. Laurent would be his only war command. “I was too late for the first war,” he observed begrudgingly, “and I’m too old for this one.” (Twatio).

Fate had something else in mind.

St. Laurent was taken off convoy duty with Restigouche and Fraser, all three heading to Portsmouth to serve as emergency reinforcements for to assist stranded British and French soldiers at Dunkirk (Dixon). DeWolf was tasked with taking St. Laurent to Le Havre, France, to evacuate some British soldiers on June 9th. As they approached the shoreline, lookouts scanned the beaches for hours. Aside from damaged equipment and smoldering ruins, the area was empty. Undeterred, DeWolf ordered his ship further up the coast, believing it possible the soldiers were forced to evade enemy patrols. The next two days they swept the area, noting only the devastation wrought by the Nazi war machine. Finally, his persistence paid off – on the 11th they rescued a small group of French soldiers who’d been hiding from the enemy. As they were brought aboard, a hidden German artillery gun began firing, shells splashing around the destroyer. From the bridge, DeWolf observed the shots and calmly ordered St. Laurent to return fire. Her guns responded, slowing the destroyer as several salvos flew ashore. Explosions and puffs of dirt and dust were seen along the coast, momentarily obscuring their vision. As it settled, he noted the gun was still intact. Although tempted to continue, he knew his mission was to bring the soldiers back to England. Thus, he ordered the ship to head back into the channel.

At the time, it likely didn’t feel as if they’d done anything special. However, DeWolf had just fired the RCN’s first shots of the war.

After dropping-off their guests and replenishing stores, St. Laurent proceeded to escort troop convoys from Canada, Australia, and New Zealand before being tasked with escort duties with Western Approaches (Douglas et. al). Early in the morning on July 2nd, two days after having been promoted to the rank of Commander, DeWolf accompanied the battleship HMS Nelson off the Irish coast when the ship’s radio office received destressing news: a nearby passenger liner had been torpedoed by a U-boat. SS Arandora Star, carrying 86 enemy POWs, as well as 734 Italian and 479 German internees, had left Liverpool without escort, destined for St John’s Newfoundland. However, before the ship could enter the North Atlantic, U47 fired a single torpedo which slammed into liner’s starboard side. Her hull-plates blew open, water flowing into the aft engine room and disabling the ship’s “turbines, main generators and emergency generators” as well as “…[knocking] out all lights and communications aboard.” (Dorling 73) Arandora Star was sinking approximately 125 nautical miles northeast of Malin Head, Ireland.

DeWolf considered the news and began issuing orders. He would head straightway to assist the doomed liner and hunt the U-boat who sank her. At speed, St. Laurent made for the Irish coast, arriving 4.5 hours after the attack. Putting his vessel at extreme risk, he brought the destroyer alongside the survivors, all huddled in lifeboats and rafts, and had scramble nets put over the side to allow the sailors to climb up. Thankfully, the enemy was long gone by this time and DeWolf managed to rescue 857 survivors. One aboard, the survivors were crammed into mess decks and any free space available. Some of the crew took up arms and were temporarily tasked as guards for the POWs.

A citation was awarded to DeWolf for saving the crew, as well as his efforts during the Dunkirk evacuation (although the latter would be awarded in 1943). His first Mention-in-Dispatches (MID), awarded on the January 1, 1941, read: “For outstanding zeal, patience and cheerfulness and for never failing to set an example of wholehearted devotion to duty without which the high tradition of the Royal Canadian Navy could not have been upheld.”

Before leaving his command, DeWolf narrowly managed to avert disaster aboard his vessel. Strolling the deck, observing the crew busy with husbandry duties, his eyes took interest in one particular sailor. The young man was crouching by a live torpedo, a paint brush in hand. Dipping it into the bucket, he applied the paint, and then, without hesitation, lifted the weapon’s safety catch and firing handle to paint underneath (one supposes he wanted to be thorough!). DeWolf shouted, moving to stop the sailor but it was too late. In his own words, “The torpedo fired, naturally, and ran wild on the deck, slammed into the deckhouse, bounced off and kept charging around. Everybody, including me, was scared.” (Cohen)

The sound of the spinning propeller joined with the loud bangs of steel on steel, the weapon seizing like a fish out of water. The paint can flew in the air and emptied its contents as sailors dived, jumped, and ran for safety. DeWolf told everyone to get clear while he focused on the large, 6-foot, cylinder bouncing unchecked on his deck, its spinning propeller threatening to shred flesh and bone. The blunt force of the torpedo, at over 500lbs, was dangerous enough, but of greater concern was the explosive charge – if detonated, it could easily blow the destroyer apart. For that to happen, it needed to run-out a certain distance before the warhead would arm itself. With each rotation of the propeller, the weapon came closer and closer to its preset limit. DeWolf couldn’t let that happen. Grabbing one of the crew by the shirt, he pulled him close and explained the plan. They were going to stop it.

“We got astride it,” he would retell. “It was slippery as a greased pig and we thought its propeller might cut our feet off. We rode and guided it over the rail and stuck one leg over the rail to hold it steady. The propeller was making a tremendous racket on the iron deck. We finally managed to release the air cock.” (Cohen)

The compressed air escaped from the weapon which, gradually, stilled. Only then, did both DeWolf and the sailor, legs, arms, and hands all covered in grey paint, sigh in relief. That was close! The captain patted the man on the shoulder – their quick actions had saved the ship, as well as the lives of all aboard.

DeWolf eyed the cylinder leaning against the rail.

“We still had a live torpedo.” He would later explain (Cohen).

Rather than risk moving it, he decided to secure it in place. Once in calmer waters, they’d unload the explosive.

“When we got to port [in England] we hoisted it on the wall and left it there. I reported to headquarters, but I don’t know what became of the torpedo.” (Cohen)

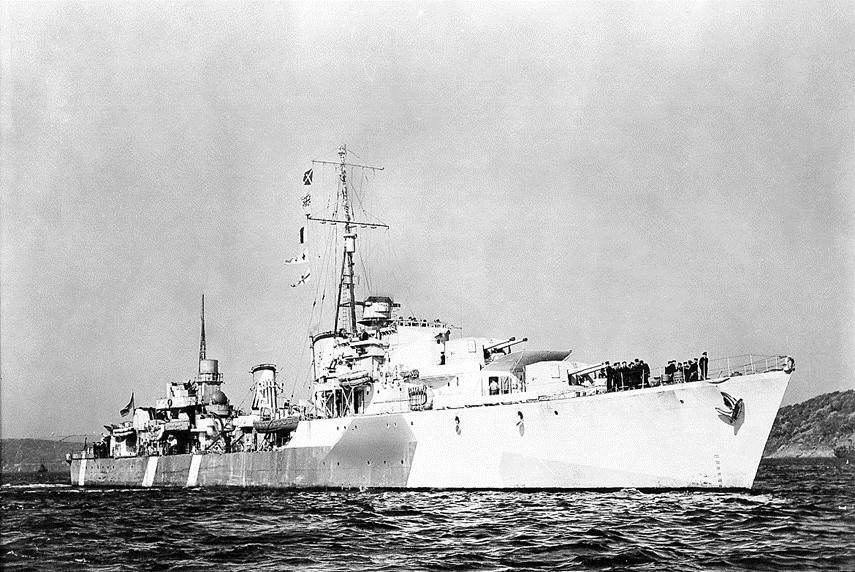

By mid-August, 1940, DeWolf was posted back ashore at HMC Dockyard in Halifax as Staff Officer Operations reporting to the CO Atlantic Coast. More than a year later, he was then made Chief Staff Officer at HMCS Stadacona, followed by a stint at Venture before moving back to NSHQ as Director of Plans for the Naval Intelligence Section. His second MID came in January 1943, “For valuable services in command of HMC Destroyer (HMCS St. Laurent) in the early months of war in Convoy Escort duty in the Western Atlantic, and overseas during the evacuation from France.” As usual, DeWolf humbly accepted the award. While these shore positions were assisting his career, and likely opening doors for future flag positions, he still felt a strong desire to be at sea. His age came to mind again and as the weeks passed, he grew restless with being away from action. Eventually, DeWolf began pressuring his superiors for another command and his persistence paid-off. As the summer neared, DeWolf was appointed first CO of a brand-new Tribal-Class Destroyer, HMCS Haida, and left for England that summer. It would be his most famous command and, under his leadership, Haida would go down in history, not only as “the Fightingest Ship in the Canadian Navy” but one of the most battle-hardened vessels of the entire war.

The legend of Harry DeWolf was about to begin.

Haida, launched on August 25th – only five days before her commissioning. The vessel felt, smelled, and even looked like a new ship. Fresh paint, clean, and void of rust and wear. After a modest ceremony, where DeWolf spoke amidst the “staccato noise of riveting hammers from other fighting craft under construction” (Sclater), the ship slipped and went straightway to conducting trials in Scotland. Questions arose among the crew regarding the destroyer’s new captain: “what was he like?”, “was he stern?” “did he have much experience?” and “could he handle a ship?” For many, this was their first ship and they’d never heard of him. On the other hand, a few of the seasoned ratings knew him by reputation, while even fewer served with him on previous ships. The responses were much the same: “[he] knows his stuff [and] can sure handle a ship.” (Sclater) An older salt, who’d been aboard St. Laurent during DeWolf’s command, summarized the man as “strict and God help the man who doesn’t know his stuff, but he’s fair. He was brought up in the old school. He’s a destroyer man.” (Sclater)

By the end of September, DeWolf received his first orders: he was to take Haida to Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands, just north of the Scottish mainland, and join the “big fellows” of the British Home Fleet. She was tasked with the infamous artic convoys, supplying critical supplies in aid of the soviets. The most direct route was to the north, through the Norwegian Sea, but the passage was fraught with danger. To reach the ports of Murmansk and Archangel, allied convoys were forced through a narrow passage. On one side were dangerous flows of thick, polar ice while, on the other side, heavily defended territory replete with mountains. German aircraft patrolled the coast, U-boats and surface raiders routinely swept the area, and the weather could be unpredictable. And that was during the warmer months – during the winter, the passage became more dangerous as artic ice pressed deeper south and created a bottleneck to the north. A convoy could easily find themselves trapped by ice and at the mercy of enemy bombers.

News of Haida’s mission swept through decks like an icy wind, giving the crew “quite a jolt.” (Sclater) The scuttlebutt about the Murmansk convoys was grim. Some warned they were the “toughest passage of them all,” while others simply noted “it was bloody.” (Sclater) Nobody was enthusiastic about it – even the officers were anxious. The ship’s navigator was reported to have ordered himself a double rum from the wardroom steward when he heard the news. Turning to the other officers, he declared “might as well fill up with anti-freeze now.” (Sclater) Only DeWolf appeared unphased by the news, acting like it were any other day. If he was at all concerned – and he likely was – he kept it to himself. DeWolf knew the importance of showing confidence and calm around the crew. Outward signs of stress or worry could devastate morale.

On November 15, Haida undertook her first of many escorts, protecting JW 54A, bound for the Kola Inlet. Sailing northward from Scapa Flow, she joined the convoy and proceeded to her escort station. The merchant vessels were all crammed to the deck with supplies – crates of ammunition, guns, tanks, vehicles, and medicine to aid the besieged Russians. These hulks never moved quickly, but by the looks of them, they’d travel even slower than usual.

Still further north they travelled, the days growing shorter and shorter until “the only sign of noon was a feeble flicker on the Southern horizon.” (Sclater) Sailors on deck were at times treated to the overhead swirls of greens and blues that made-up the aurora borealis. A few joked that the name ought to be changed to the “southern lights” as they were presently so far north that they appeared to the south of the destroyer. Eventually, ten long days later, they reached their destination without incident. To many it came as a surprise, convinced as they were that an attack was guaranteed. Nobody complained and DeWolf acted as he always did, as if he’d expected it to turn out that way.

After a brief layover, they escorted RA 54B back to Loch Ewe. Again, they suffered no losses on the return trip. Some of the crew questioned the stories – perhaps they had been worried for nothing?

Things changed on December 20th. Haida was escorting another convoy when they came across the 770-foot German Battleship, Scharnhorst, an imposing vessel, heavily armed and built for a single purpose: to sink ships.

It was apparent from the outset that things would be different this time. Only a day into their trip, Haida’s lookouts reported seeing enemy reconnaissance planes in the sky. Two days later, U-boats were sighted behind them, shadowing the outer edges of the large convoy. It didn’t concern DeWolf – he asked only to be kept informed regarding their whereabouts and positions. The reason was that prior to departing, all captains were informed that this convoy had a dual purpose: in addition to delivering supplies, Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser planned to lure Scharnhorst out into open water. It was a trap.

It made for a bleak Christmas. DeWolf noted that the day “…was spent at sea under unusual conditions – in the Arctic, in bad weather and almost constant darkness escorting a straggling convoy, shadowed and reported by enemy aircraft with the Scharnhorst and an unknown number of U-boats in the vicinity.” (navalmilitarymuseum).

The entire convoy remained alert. On the following morning, Haida, along with HMCS Huron, shielded the merchant ships, guiding them like sheepdog away from where the larger RN battleships and cruisers pounced on Scharnhorst. Haida was the stern escort for JW55B, DeWolf acting as second senior to Captain McCoy in the O-Class Destroyer Onslow (Dixon). The mighty Nazi ship had taken the bait, moving out to attack the convoy unaware of the attack force awaiting her. From Haida’s bridge, DeWolf couldn’t see what was happening (the forward most escort destroyer for Scharnhorst crossed within twenty-miles of Haida), although at times he couldn’t tell if he could just make-out the muted sounds turrets firing or if his ears were playing tricks on him. It didn’t matter – his attention was on the ships ahead.

He braced against the bite of the artic wind, which found its way through the layers of his clothing. The spray off Haida’s bow splashed as they broke through the waves, hardening into a layer of ice along the upper deck and rails. He tried his best not to think of his unsettled stomach. Soon, sailors would move out with axes to chop away at it and minimize the extra weight on the ship (too much build-up could cause the ship to turtle over). DeWolf knew from his training and experience that he needed to remain vigilant – an inattentive captain made for a slacked crew. And with the wolfpack prowling these waters, he needed everyone at their best.

The convoy would be well into Russian waters when news came of the outcome of the battle, a simple message stating “Scharnhorst had been sunk.” (Sclater)

Three days later, a squadron of German bombers – Junkers Ju 88s – appeared overhead, along with U-boats astern which began to follow the convoy. DeWolf ordered the crew to Anti-Aircraft Action Stations, suspecting reprisal for the loss of Scharnhorst. He didn’t hesitate and ordered all escorts to engage the enemy. From land, bombers came over the mountains to attack, but appeared surprised to find bullets already spraying from the warships. The pilots reacted, jerking the controls and rolling their aircrafts to avoid the steady lines of tracers. A few hastily dropped their payloads, more to reduce weight than attack the convoy. Large geysers of water erupted harmlessly in the distance while enemy aircraft retreated to land.

DeWolf figured the U-boats would be next and ordered Haida into a hard turn, coming about and readying a depth charge pattern. The destroyer sped towards the enemy, too quick for them to chance a wild shot at the merchant ships. Instead, they dived and hid to avoid a fight with the Tribals on the surface. DeWolf gave the order and the officer beside him, phone receiver to his ear, relayed the message aft. With a crack, two depth charges flew from side launchers and another eight rolled-off the stern rails. For a moment, the sea behind Haida turned into a frothy line of successive underwater explosions. None of the U-boats decided to stick around. On December 29, 1943, the entire convoy reached their destination. In the new year, Haida was finally back to Scotland and, after some time ashore, sailed for Plymouth, arriving on January 10, 1944.

Entering Devonport’s Dockyard, DeWolf ordered fenders over the side and lines/wires made ready. His crew were “unusually proud of the way he handled” (Sclater) the ship, and DeWolf was in known for his proficiency at berthing a destroyer. It was no easy feat, but Haida’s captain made it look effortless: “it was done in a swift, competent manner that never failed to bring a look of surprised admiration to the faces of the waiting dockers, which was a tribute of some gratification to the crew.” (Sclater) But with the return to sun, fairer weather, and longer days also came new threats, principally from enemy E-Boats. The channel was a deceptively dangerous place – under daylight things were relatively calm but at night, it flooded with coastal vessels bent on attacking shipping and taking out enemy patrols. These fast and small vessels were well armed and difficult to pinpoint, and while some were armed only with guns, others sported torpedo tubes on their hulls. Combined with frequent aerial patrols, minefields, and shore batteries, ships took great risks traversing these waters.

Things were changing in the war. Senior Allied Commanders knew it was necessary to land ground forces into Nazi occupied territory and that required vulnerable amphibious craft crossing the channel. To facilitate this, the allies decided to change tack and actively hunt enemy surface vessels operating from ports in the Bay of Biscay. These anti-shipping operations were known by codenames “Tunnel” and “Hostile” – Haida would now find herself moving from guardian to predator, her new mission to make the surrounding waters safe by sinking enemy ships. But first the crew would have to learn how to fight at night against these new threats. It wouldn’t be the same as on convoys – the enemy moved fast, in complete darkness, and was as interested in sinking warships as merchant vessels. Haida joined the 10th Destroyer Flotilla (DF) and the ships practiced hunting each other throughout the month of January. By February, they were ready.

While some vessels laid lines of mines across portions of the English Channel, ships of the 10th DF embarked on their first operation. At the bridge, DeWolf watched the bow of his ship nose her way through the sea-gates and proceed into open water. A light breeze brushed across his face, the last light over the harbour succumbing to a growing darkness. They were bound for the French coast and, from this point, actively scouting for enemy ships. He’d told the crew to ready themselves for a fight – it was time to turn the tables on the enemy and hunt the hunters for a change. They might have been surprised and, possibly, disappointed when they returned the next morning without incident. It would be that way for the next two months. There were some false alarms – a small farm on an island was mistaken for the silhouette of an enemy ship while, during another patrol, a shipping boat was reported to be an enemy E-Boat. Thankfully, they realized the error before attacking either one.

Things changed on the night of April 25/26th. After a stint ashore with the captains of two other Canadian Tribals – LCdr John H. Stubbs and LCdr Herbert S. Rayner – for briefing at Area Combined Headquarters, DeWolf returned to Haida with orders in hand: they were to slip that evening and “… carry out Operation Tunnel… Destroyers Haida, Athabaskan, Huron, Ashanti will slip at 2100 and proceed in company with H.M.S. Black Prince.” (Sclater) He went straightway to his cabin to make preparations, instructing the galley prep an early supper. DeWolf ate a quiet meal before dressing in his sea gear and heading to the bridge.

Haida slipped her moorings and again headed out to sea, as she’d done countless times during the previous months. It was routine at this point, even waving at onlookers ashore as the destroyers exited the channel. Still, something felt different this time – DeWolf sensed the fight to come. Gunners quickly checked their weapons, firing a few red tracers into the night, before the captain ordered “darken ship”. Out into the night of the channel they went, and as planned, action stations were called shortly after 2200hrs. On the bridge, DeWolf listened as reports came through the various brass voice pipes and phones. Along with him were the action officer of the watch, gunnery and torpedo observer officers, and singalmen by the flag locker. He sat on a tall wooden chair – the captain’s chair – and stole a glance at the stars above before glancing past the funnel. Haida’s sister ship, Athabaskan, followed closely behind to starboard. It was a moonless night with no clouds and clear visibility – DeWolf reported he could see nearly two miles out from the open bridge. Favourable conditions for combat if they indeed came across the enemy this night.

Over the next two hours they proceeded in a steady pattern, cautiously approaching occupied France. The two tribals formed the port sub-division of their patrol force (Force 26), with HMS Ashanti in the distance to the port and Cruiser HMS Black Prince at the vanguard. Around 0100hrs, a light in the distance appeared, long enough for the navigation officer below the bridge to plot it. Ten minutes after that, a search light shone up in the sky. Below the bridge, the navigator at his table commented “must be looking or planes” as he made his calculations.

DeWolf wasn’t as convinced and continued to scan the coastline with his binoculars when another gun battery fired, the flash a mere spot of light in the distance. He checked his watch – 0125hrs – and then waited to see where the salvo landed. Neither he nor the lookouts noticed, and he wondered if they were even aiming at their vessels. After a couple of minutes another searchlight illuminated, followed by several more ‘pops’ of gunfire. They counted ten salvos in total, none remotely close to any of the ships of Force 26 but convincing them they were indeed the intended target (NavalMilitaryMuesum). The flotilla’s Senior Officer (SO), somewhere ahead in the cruiser, ordered the tribals to alter their course away from land, but no sooner had DeWolf instructed the helmsman did Black Prince detect something ahead on their radar. Multiple contacts, all strong signals. DeWolf received word that as many as five ships were in the distance and altering course back to the coast.

“Not likely,” DeWolf might have thought as he ordered Haida’s engines to 28 knots. Then, at 0212hrs, another order from the SO came – “increase to maximum speed to close and engage the enemy.” (Sclater) DeWolf could feel the engines working throughout the ship, the bow splitting waves into a long line of white plumes astern. Both tribals, commanded by seasoned captains, were closing-in on the enemy and DeWolf felt relieved having the young west-coaster along with him. Stubbs was a gifted skipper, second-to-none in seamanship, and DeWolf knew he could count on both his professionalism and resolve.

Ahead a starshell from Black Prince streaked high into the night. As per the plan, the cruiser would illuminate the enemy while the destroyers moved in for the kill. DeWolf and the rest of the bridge crew watched the flare as it rose into the sky, awaiting the inevitable explosion that would reveal the enemy vessels. Unfortunately, the angle was off – too much to the right. DeWolf sent a signal to Black Prince – “more left”. The cruiser’s guns moved and fired again. This time the starshell burst revealed the enemy, a grouping of small dark bumps just below the horizon.

“Open fire,” DeWolf ordered and the gunnery officer relayed “commence, commence, commence” into the appropriate telephone (Sclater). Thirty seconds passed before Haida’s A and B guns opened, sending four shells into the distance. The “ship heeled with the recoil” (Sclater) and the familiar smell of cordite – a smokeless, cord-shaped propellant – filled the air around them. They watched the shots, visible as they were tracer rounds, arch towards the targets, although they didn’t appear to score a hit. Athabaskan, Huron, and Ashanti joined in and soon all four tribals were repeating the drill, launching multiple salvos at the enemy while Black Prince continued to expose the enemy with starshells (additionally, the cruisers used another turret to launch its own attack). The German ships were making smoke and trying, without success, to outrun Force 26. Flashes in the distance signaled the enemy returning fire, but their starshells and rounds were off target. The enemy had yet to pin-point them. Aboard Haida, rangefinders locked-in and soon reports of hits and fire on two German destroyers were relayed to DeWolf on the bridge. Around 0248hrs the cruiser’s B turret malfunctioned, preventing further starshells. The enemy fired torpedoes, thankfully reported by Ashanti. The cruiser veered off to avoid the attack while the tribals kept up the pursuit, now under DeWolf’s leadership.

At 0313hrs the enemy slowed and were now near 5,000 yards from Haida and the other destroyers. Athabaskan and Ashanti fired starshells while the other two engaged. DeWolf, suspecting the enemy had slowed to launch torpedoes, turned his ship hard over, the forward gun mount firing and scoring several hits on the distant enemy. He then brought his ship hard to starboard to continue the pursuit.

DeWolf would later become known for these hard movements at speed, enabling his ship to dodge while not losing momentum. The crew affectionately called him “Hard Over Harry” (Dixon).

The enemy could now be identified – an Elbing Class destroyer. DeWolf focused on it, resolved to destroy the vessel. Haida again fired, catching the enemy amidships and punching through her hull plates. The rounds exploded somewhere within, wreaking havoc. Successive shots struck aft as well as just below the bridge. Steam burst through her wounds, the engines faltering and forcing the vessel to stop. There was no escape now. Fire spewed out from the holes left from Haida’s hits and quickly spread across the deck. At this point Stubbs had brought Athabaskan’s guns on the crippled ship and, shortly thereafter, Huron and Ashanti joined in (they had lost the ships they were pursuing) All four pummeled the Elbing, bit by bit breaking her apart. From the bridge, DeWolf could see it all – the fire, heat, and hissing noise as water cooled the hull, now nearly glowing red from internal flames. Some sailors aboard the doomed vessel attempted to ready a raft just as a salvo from Haida struck the hull, sending the “… raft and occupants hurtling skywards in a shower of debris.” DeWolf regretted it – he took no pleasure in cutting-down sailors attempting to flee – but since the enemy’s guns were still retaliating, albeit erratic, he had to keep-up the pressure. Later, he would describe in his report “the enemy came to life at this stage and put up a spirited close range fire, in spite of the fact that the ship appeared quite inhabitable….” (Sclater)

Finally, after thorough thrashing, the Ebling (later identified as T-29) rolled to port and sank at 0421hrs. Haida’s crew cheered and when the ship headed back home, the SO sent word for the destroyers to “wear battle ensigns on entering the harbour.” (navalmilitarymuseum) For the first time, Canadian ships had sunk a surface raider.

Damage sustained during the fight had been reported by various departments to DeWolf. During the engagement, as they circled T-29, one the Ebling’s 20mm scored several hits on Haida, punching holes into the engineer’s workshop, sick bay, and two more punctures into the after funnel (Dixon). Unfortunately, DeWolf’s day cabin was also hit. The old man went aft to survey the damage, stopping last at his cabin where he beheld the almost baseball-sized holes in the bulkhead behind his desk. But what bothered him more than anything was that the rounds had taken the heads off the golf clubs in a bag (Dixon). His mood immediately soured, and many former crewmembers would later testify that “Harry became highly motivated to sink ships” (Dixon) after that***.

During the battle, both Haida and Huron fired their torpedoes at the enemy but none of them found their targets. It was later determined that they were likely set too deep and the Admiralty Tactical Section later rebuked them for “their incompetence in torpedo attacks.” (Dixon) DeWolf didn’t appreciate the criticism and henceforth “vouched to use guns only” in battle (Dixon).

Haida was back out the night of April 28/29th. Eight Motor Launches (MLs), escorted by two Motor Torpedo Boats (MTB), were to conduct a mine laying operation off Ile de Bas but command had received news that two Elbing Class Destroyers had been spotted in the area. Hadia and her sister ship Athabaskan were sent to prevent the enemy from interfering with the coastal forces operation. DeWolf, now acting as the SO, took the lead and led Athabaskan out into the channel around 2215hrs. It was another night of favourable conditions – a full moon and clear sky provided the most visibility yet. Remaining on the bridge, sitting on his chair with his binoculars slung around his neck, DeWolf seemed keen to engage and sink more ships. Just after midnight, Haida’s plot picked up a signal, two mid-sized ships with a possible third heading west along the French coast. DeWolf sent a message to Stubbs to move at speed and intercept. They were hot on the trail of T-27 and T-24.

If DeWolf was feeling any excitement, it didn’t show. He was, as always, characteristically calm. The crew felt their captain was confident, a professional who knew what he was doing. It gave them confidence and they’d grown fond of him.

After 0400hrs, Dewolf sent a message to command: “Have made contact with two enemy ships and am closing to engage.” (Sclater) The enemy were within 7,000 yards now and DeWolf, with raised binoculars, gave the order “Ignite”.

The Illumination Control Officer picked up his phone and instructed X gun to fire “three stars, spreading left, five.” (Sclater). Once spotted, DeWolf gave the order to open fire on the enemy. Hadia’s forward gun fired, the destroyer rolling slightly with the force of the blast. Stubbs also ordered Athabaskan to attack, launching his own starshells followed by shells from her main gun. The Eblings immediately made smoke and turned east to head back to the French coast, firing torpedoes towards the Canadian destroyers to cover their escape. As was characteristic, DeWolf made a hard 20 degree turn to evade the attack before swinging the ship back on course.

“Athabaskan’s been hit,” a voice called.

It was 0427hrs, and Haida’s log would note “Athabaskan blown up!!!!” (Dixon) The news caught DeWolf off guard, a knot twisting in his stomach. Nobody had seen the attack. Astern, a large flame rose into the night from somewhere behind Athabaskan’s bridge. The ship fired B gun in defiance, but the sight of the burning tribal was an easy target. The enemy now concentrated their guns on her and Athabaskan lost propulsion, slowing to a stop.

DeWolf sprang into action, ordering Haida to make smoke to screen Athabaskan from attack. Haida, turned hard to starboard, it’s funnel belching a cloud which blanketed the space between Athabaskan and the enemy. It wasn’t perfect but at least prevented the enemy from pinpointing her exact location.

Haida, now alone, bore down at the enemy. Rounds crisscrossed, Haida scoring a hit on T-24 and setting it on fire. DeWolf observed the second destroyer slowing behind the first, turning to make a run for the coast. He ordered his guns to train on T-27, and soon salvos landed on the other destroyer, ripping through her superstructure and deck. Just then a loud explosion drew their attention again astern, where in the distance they saw another, even larger fire, spewing up into the sky from their wounded sister ship.

What the hell had happened, they all wondered …

Stubbs had just given the order for the crew to head to “Abandon Ship” stations when, without warning, another blast erupted from the afterpart of Athabaskan, followed by and explosion which blew parts of the vessel along with hot oil in all directions. In short order the ship sank astern, her bow raising high into the sky before sliding beneath the waves.

Haida, thick in the fight, continued firing on the ship, “a double motive now, surged forward for the kill.” (Slcater). T-27, now burning from successive hits, went aground and the Officer of the Watch warned DeWolf that reefs were dead ahead. He ordered “port 20” – another hard turn – and the ship tilted sharply to avoid the hazard. He’d not yet sunken the enemy but the thought of Athabaskan and Stubbs were heavy on his mind. His mission was to sink the ships, so he swung Haida around continued the assault until the Ebling exploded.

It was now nearing 0500hrs and the morning sun would soon begin its rise over the horizon, exposing the ship to shore batteries and air patrols. DeWolf couldn’t risk chasing down the damaged T-24 which was making a dash for the coast. Instead, Haida went back to rescue survivors from Athabaskan. The smoke from their screen still lingered over the waters and DeWolf ordered a starshell to be fired to help find survivors. Many were huddled in clumps and covered with oil. DeWolf carefully brought the ship alongside, cutting the engines and gliding to their shipwrecked comrades. With the exception of Haida’s gun crews, the captain ordered “every man who can be spared” to head immediately “to the maindeck and help bring survivors aboard.” (Sclater). Additionally, he directed all boats that hadn’t been damaged during the fight to be lowered, including putting life rafts over the side (starboard seaboat and whaler were both riddled with 20mm fire from T-29) ****. They were to be unmanned although some of Haida’s crew would voluntarily go in them to help rescue survivors. He checked his watch, his mind making some quick calculations.

“We shall wait for fifteen minutes – bring as many on board as you can,” he concluded. (Sclater)

The order would later haunt DeWolf. His heart wanted to stay until every survivor was rescued, but a captain couldn’t let their personal feelings endanger the life of their ship or crew. With dawn would come new threats and the loss of all cover, making his ship an easy target.

Haida’s engine had stopped and the ship now drifted with the wind, moving towards the survivors on the port but away from those on the other side. Some survivors were unaware that the ship was Haida, and fearing being taken prisoner, began to swim away from the destroyer. DeWolf, leaning over the bridge wall, encouraged the stranded to swim with all strength to the scramble nets that had been flung over side and assured all they were friendly. But for many, the cold and oily water made it too difficult to muster the strength to haul their bodies up to the main deck. Many of Hadia’s crew bravely climbed down to assist them. Two officers and four ratings had even formed a line on one net to help survivors make it on deck (Sclater). It was slow going – DeWolf again checked his watch. They were well past the fifteen minutes he’d given. The sun was rising and they could plainly see the coastline in the distance. A call came-up to the bridge and DeWolf approved the starting of the ship’s engines. He didn’t have a choice.

“We are now going Slow Ahead,” he would later note, adding that leaving was “the hardest decision of his life.” (Dixon)

Slowly, Haida began to move. To the port, a raft with oil-covered sailors came along side, making fast a line to the net. A voice urged that the wounded, burned by the hot oil, be taken first. Then, after some tense moments, the same voice bellowed out “Get away Haida, get clear!” Those assisting the wounded up the nets would later confirm that it was Stubbs, Athabaskan’s captain. He was hanging onto the side of the raft, resting on burned arms, having insisted that the spot offered to him be given to a more gravely injured sailor. The ship pulled away, snapping the line that had tethered the raft to her hull. They drifted into the darkness while officers and ratings tried to haul up the nets to bring the last survivors aboard, but as the ship gained speed, oily hands faltered, and the men fell into the water.

Stubbs, along with 128 of Athabaskan’s crew, would never be seen again. 42 had been rescued by Haida while another 85 would be later taken prisoner when discovered by enemy patrols.

A somber mood fell over the ship. On the bridge, DeWolf focused with steely eyes on the task ahead, putting on a brave face. He’d perfected the art of maintaining his command presence, but perhaps those near him could see through the mask. He radioed Plymouth, requesting fighter cover (Dixon).

Inside, DeWolf wasn’t alright. He was speeding away from shipmates, fellow Canadians. The crews of the two vessels were close – Athabaskan was after all their sistership – and Stubbs, who hadn’t been recovered, a close friend. He quickly shook up his crew, warning that air attacks were likely and to be ready to fight their way home. Hadia was now fully exposed and on the wrong side of the channel. The enemy would be looking for payback.

Thankfully, two destroyers (Offa and Orwell) appeared in the distance and formed-up with Haida. Only then did DeWolf allow himself to relax and gave the order to stand-down from action stations. As they entered harbour, the ships they passed each saluted in turn. DeWolf, who’d remained on bridge the whole time, now supervised the evacuation of all wounded from the ship. In a splendid display of comradeship, a volunteer party from Huron mustered alongside to assist the battle-fatigued crew with repairs and clean-up from the battle. They took on the lion’s share of chores and did so with gusto. Sclater put it best: “For their understanding hearts and the help which was given, unsought and unrequested, Haida was grateful in a way that went far beyond words.”

The following month offered little respite. After a few days of rest and repairs, Haida was back out at sea. On May 4th, she took part in a bombardment exercise as a lead-up to Operation Overlord. During this month, Haida also participated in an additional three Hostile operations along with drills to prep for the June invasion of Normandy. DeWolf received some welcome accolades and recognition of his meritorious service. On May 27th, he was duly awarded a Distinguished Service Order, second only to the Victoria and George Cross (respectively), for “… gallantry and distinguished service as Senior Officer of Destroyers in successful destroyer night actions in the English Channel on 26th and 29th April 1944.” Then, on June 1st, he was promoted to the rank of Captain, earning his fourth bar on the sleeve of his tunic. Four days later, Haida set out on Operation Neptune, patrolling convoy lanes guiding vessels to their amphibious assault points off the French coast. D-Day was about to commence, but so far Haida was mostly inactive, the crew watching as hundreds of aircraft flew overhead across the channel.

DeWolf was growing impatient – he wanted another scrap and his crew felt the same way. Haida now prided herself as a fighting ship and so when DeWolf received intelligence that two Narvik Class Destroyers, a repurposed Dutch destroyer, and a Elbing destroyer (T-24) had been spotted leaving their port at Brest, he jumped on the task. On June 8th, Haida and the 10th DF, were put on high alert. Overcast skies and rain greatly impacted visibility and it was assumed the enemy destroyers would attempt to attack the lightly armoured supply chain. Orders came at 1637hrs – they were to head towards the coast between Ile de Bas and Ile Vierge and join Force 26. By 2200hrs they were on the lookout for the destroyers. DeWolf and the 10th DF moved south towards the French coast, zig-zagging back and forth through their patrol area. Over the next three hours they conducted a careful search but, turning up nothing, proceeded back west.

Various echoes were detected on radar, too faint to identify. The weather and low ceiling was interfering but, eventually, the signal improved and the SO ordered the ships on an intercept course. At 0124hrs, they spotted the enemy who promptly fired torpedoes at the approaching ships before turning to retreat. Haida, along with others, evaded the attack, DeWolf ordering the ship hard over as was his style. They soon opened fire, Huron taking-on Z-24 and T-24, scoring hits on both ships.

The rain was blowing harder, making visibility worse than before. DeWolf strained to focus on the distant ships, his binoculars pressed firmly to his eyes and cursing the droplets forming on the lenses. The enemy was making smoke and soon vanished from sight. Before long, Haida and Huron could no longer distinguish between vessels and so DeWolf checked his guns to avoid a friendly fire incident. The captain was growing frustrated – he wanted the enemy sunk but the weather wasn’t cooperating. By 0215hrs, he was forced to give up the search and rejoin the rest of the flotilla.

Ten minutes later, Haida’s radar picked up another contact. He couldn’t be certain about their identity – they could be friendly – and sent a signal via aldis lamp. When the signalman reported an unintelligible reply, DeWolf suspected the ship wasn’t friendly and closed the distance between them, repeating the signal challenge. This time the ship didn’t reply, but he couldn’t be certain it wasn’t HMS Tartar, the SO’s ship, which had taken damage. Perhaps her signaling equipment had been disabled? He cursed the weather – they still couldn’t identify the destroyer – and Haida and Huron came astern the vessel. Just then, the mystery destroyer turned south and dropped a smoke float to mask her escape. There was no doubt now – the tribals pursued and launched starshells, revealing Z-32. The enemy was fast, making just over thirty knots, and quickly began to widen the distance between them. Then, at 0311, the destroyer made a sharp turn to port and proceeded into an allied minefield.

DeWolf kept his ships away from the danger and moved around the obstacle. The range between them and Z-32 increased to over 18,000 yards and they lost contact with the destroyer. Refusing to give up, DeWolf continued on course and twenty minutes later, managed to regain contact with the ship – somehow the enemy had made it through without setting off a mine. Their guns were still out of range. Then, for reasons that remain unknown, Z-32 decided to turn south, allowing the two tribals to close to 7,000 yards and attack. The enemy promptly responded with a salvo that landed around fifty feet ahead of Haida – a near miss. Salvos from the tribals found the enemy, who then turned into another allied minefield for cover (again making it across without incident), before coming around to Hadia’s portside. All three vessels were nearing a patch of rocky, shallow water, but the tribals kept-up the pressure, eventually forcing Z-32 onto the shoals off Ile de Bas. The destroyer, having ran aground, began to smoke. At 0525hrs, one of their shells started a fire which spread over the ship. Another victory for the Canadians. DeWolf ordered the ships to disengage and rejoin the task force. That morning they again entered port with battle ensigns aloft.

The Canadians were developing a fierce reputation among allies and foe, chiefly Haida and her bold captain.

DeWolf was back out with the 10th DF on June 12th, again accompanied by Huron, but this time they were undergoing a clandestine mission. An army major, accompanied by a slew of signalmen and special equipment, were brought aboard under much interest and security. DeWolf was to take them around the channel islands whereby their guests would pass bogus messages, under the guise of secret communications, about another amphibious raid. The hope was to trick the enemy out of port, lessening the force defending Cherbourg and open it for capture. After midnight, Haida and Huron moved towards the coast and watched as allied aircraft dropped bombs on shore defences. The crew were only mildly interested with the display. While the “fireworks” were nice, they’d much rather be patrolling.

By the end of the month, Haida had racked-up a handful of anti-submarine patrols. On the 24th, she was tasked by the Commander-in-Chief Plymouth to accompany HMS Eskimo thirty miles south of Land’s End. An aircraft had spotted the cylindrical shape of a U-boat on the water and now Haida was searching for signs of it. The conditions were excellent – a brilliant blue sky, bright sun, no clouds, and the remarkably calm waters. It didn’t get any better than this.

After a few hours, lookouts aboard Haida observed an aircraft drop depth-charges at a U-boat five miles behind them. U971 had been detected by the aircraft’s radar and was now attempting to dive and evade the attack. The boat was already damaged from previous attacks, including its torpedo tubes, but it could still submerge. Disappearing under the surface, bottoming-out to confuse any ASDIC searches, U971 waited. Soon Haida came upon the spot and, with a pattern at the ready, launched depth charges into the sea. Huge explosion erupted and Eskimo followed with a similar attack. Together they swept the area a total of nine times, violently shaking the U-boat on the channel floor. U971 couldn’t take any more. German sailors were moving in six inches of water and couldn’t survive another bombardment. They either surface now or risk being stranded on the ocean floor. Around 1825hrs, their captain gave the order to blow all the ballast tanks and, as it broke through the surface, Haida opened with B gun, striking the conning tower and starting a fire. German sailors abandoned the vessel and fifty-three were rescued by Haida and Eskimo. Once again Haida returned home displaying her colours. Black Prince signaled her compliments, adding “Narviks, Elbings and submarines all seem to come alike.” (NavyMilitaryMuseum)

DeWolf sent back the reply, “A morning recreation for the crew.” (Dixon) His reputation was firmly cemented as a fire-eater *****.

Some leave was in order and the officers and crew enjoyed a few weeks ashore. When they returned in July, they were back with the 10th DF operating around the Bay of Biscay. On the evening of the 13/14th, Haida along with Tartar and a polish destroyer Blyskawica were dispatched to attack Lorient, situated at the northern end of the bay and one of the last holdings in the area yet to fall to the allies. The Nazis intended to hold it at all costs, knowing that if they lost it, their ability to wage war in the Atlantic and disrupt allied logistics would be diminished. And so, they bolstered defences as best they could, peppering the coast with slews of various-sized shore batteries and long and short-ranged radar. Additionally, there were air bases to contend with and coastal vessels at the ready.

The three ships – Canadian, British, and Polish – swept the area but found nothing. Their luck changed the next day. It was another pleasant night of mild temperature, clear skies, little wind, no moon, and tranquil waters (DeWolf likely appreciated this more than anyone else aboard). At 0209hrs, enemy ships were spotted – a convoy of merchant vessels. The SO ordered his ships to slow to twenty-two knots and wait for their prey to draw away from the coast before moving to engage. At 0300hrs, the destroyers sprang into action, launching starshells and opening with their guns. Tartar focused on a merchant steamer while Blyskawica took-on the trawler. DeWolf ordered Haida’sguns to train on the largest merchant vessel and, although escorts did return fire, the three destroyers successful sunk all three vessels while avoiding any damage to themselves. An excellent night’s work.

Haida’s next encounter occurred the following month. As part of operation “Kinetic”, she engaged an enemy convoy along with other ships of Force 26. Starting just after midnight, they attacked and nearly destroyed the entire convoy, sinking up to eight or nine vessels. During the engagement, an accident in Haida’s “Y” turret unfortunately killed two gunners and wounded eight sailors – a shell had exploded just after being loaded into the breech. The gun was now disabled but the ship wasn’t significantly damaged. When Force 26 encountered yet another convoy later that morning, Haida joined-in although they didn’t have the same success. The enemy quickly retreated, sustaining minimal damage before making it in range of coastal batteries.

DeWolf and the crew would be ashore as their ship spent some weeks undergoing repairs. Towards the end of August, Haida once again underwent offensive sweeps of the Bay of Biscay. On August 29th DeWolf was awarded a second Distinguished Service Cross, the citation published in the London Gazette reading: “For outstanding courage, skill and devotion to duty in H.M. Ships Tartar, Ashanti, Eskimo, Javelin, and H.M. Canadian Ships Haida and Huron in action with German destroyers.” (his first was for his actions on June 9th). He’d also been awarded a total of four MIDs by this point. The next day, Haida was given the honour (along with HMCS Iroquois) of escorting the cruiser Jeanne D’Arc from Algiers to Cherbourg, ferrying some fifty French government officials back to home to France. The seas around the channel and French coast began to calm as allied pressure on land and air forced the enemy back across borders. Haida helped to capture two enemy ships ferrying enemy personnel escaping Brest, the last action DeWolf would have at the helm of his ship. By the end of September, they’d be back in Halifax.

DeWolf’s command of Haida had come to an end and, under his leadership, the destroyer had racked-up an impressive list of credits, assisting in the sinking of fourteen ships, nine credited solely to her: T29, T27, ZH1, Z32, U971, UJ1420/UJ1421 (trawler), M486 (minesweeper), SC3 (escort vessel), and a Vedette Patrol Vessel.

After the war, DeWolf was promoted to Commodore in 1947 and awarded several other rare honours for his distinguished war service, including Commander of the Order of the British Empire (1946), Officer of the Legion of Merit (US), Officer of the French Legion of Honour (1947), the Croix de Guerre (1947), and the Norwegian King Haakon VII Freedom Cross (1949). He would go onto command two Canadian Aircraft Carriers, HMCS Warrior and Magnificent in 1947 and 1948, respectively, before being promoted to Rear-Admiral and appointed Flag Officer Pacific Coast. Then, in 1950 he was appointed Vice Chief of Naval Staff and, two years later, was made Principal Military Adviser to the Canadian Ambassador to the United States and served in Washington D.C. as Canadian Joint Staff. In 1956 he was promoted to the rank of Vice-Admiral and became Chief of Naval Staff (now Commander Royal Canadian Navy) – the highest appointment in the navy. He retired in 1961 after having served Canada for forty-two years, achieving the rare distinction of having three bars awarded to his Canadian Forces Decoration. When asked about his time in the navy, DeWolf commented on his struggle with chronic seasickness and how his remedies helped make him a more effective captain:

“I used to sleep or rest propped up in the bunk, because from that position, I got on my feet, I was less apt to get seasick than if I was lying down. If there was the slightest increase in the sound of voices, I knew something was on, so I’d be awakened. I got lots of rest, but I never changed my clothes.” (For Posterity’s Sake)

DeWolf moved with his wife to her home in Bermuda, returning to Canada in the summers. He enjoyed his free time, particularly playing golf, fishing, and working with the Royal Canadian Benevolent Fund. He kept a low profile, avoiding the limelight at every turn. His hometown named a portion of the waterfront on Bedford Basin in his honour in 1992.

DeWolf died while in Ottawa on December 18, 2000. He was 97 years old and was given a naval burial at sea with full honours from HMCS Ville de Québec. Fourteen years later, the RCN’s new class of Artic Offshore Patrol Vessels were named in honour of DeWolf (aka Harry DeWolf-Class) and the first ship built was named after him, launching on September 18, 2018. HMCS Harry DeWolf has lived up to the reputation of its namesake – while deployed on Operation CARIBBE, Harry DeWolf assisted in anti-drug trafficking sweeps, resulting in 357 kg of cocaine seized.

Vice-Admiral Harry DeWolf was not only Canada’s greatest naval legend but one of the most effective ship captains of the Second World War. Truly, if any Canadian deserves to be compared to Admiral Nelson, it’s him.

Footnotes

*DeWolf’s full name is listed in numerous sources, both online and published, as Henry George DeWolf. DeWolf’s son, Jim DeWolf, actually looked at his late-father’s birth certificate and confirmed that his full name is Harry George DeWolf.

** The typical age of enlistment was 18, although many underage Canadians still joined, either with parents’ consent or by out-right lying about their age. Many recruiters didn’t press the matter – proof of age wasn’t required, and many didn’t bother to challenge the applicant’s assertions. Later, during the Second World War, some applicants were as young as 13!

***According to historian Peter Dixon, DeWolf would never confirm or deny that he had the clubs stashed in his cabin but Dr. Alex Clarke found the receipt for the replacement clubs. The patch-job covering the holes is still visible in the captain’s cabin.

**** Worth noting is the gallant conduct of some of Haida’s crew who decided to stay behind in the motor cutter to help survivors. At great personal risk, the three sailors managed to save six more men from Athabaskan.

***** The term comes from Lieutenant-Commander Hal Lawrence DSC, CD, RCNVR who, along with Stoker Petty Officer Arthur Powell DSM, RCNVR, leapt aboard and captured U94 in the Caribbean Sea. Lawrence referred to HMCS Oakville’s captain during the engagement, Commander Clarence King DSO, DSC, RCNR, as a “real fire-eater”, meaning that he was keen to engage the enemy in combat.

DeWolf’s Awards and Decorations:

In hierarchical order, Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE), Distinguished Service Order (DSO), Distinguished Service Cross (DSC), 1939-45 Star, Atlantic Star with France and Germany Clasp, CVSM, War Medal, x 4 MIDs, Queen Elizabeth the II Coronation Medal, Canadian Forces Decoration with three bars, US Legion of Merit (Officer Grade), Croix de Guerre, and King Haakon VII Freedom Cross.

Sources:

Cohen, William A. Heroic Leadership: Leading with Integrity and Honor. Jossey-Bass; 1st edition (May 24 2010)

Douglas, W. A. B.; Sarty, Roger; Michael Whitby; Robert H. Caldwell; William Johnston; William G. P. Rawling (2002). No Higher Purpose. The Official Operational History of the Royal Canadian Navy in the Second World War, 1939–1943. Vol. 2, pt. 1. St. Catharines, Ontario: Vanwell.

Dorling, Henry Taprell (1973). Blue Star Line at War, 1939–45. London: W. Foulsham & Co. pp. 9, 40–45.

Peter Dixon, (HMCS Haida historian and Friends of Haida member), in discussion with the author, Burlington, Ontario, 2023.

navalandmilitarymuseum.org/archives/articles/hmcs-haida

jproc.ca/haida/dewolf.html

Uboat.net

Prepared By:

Sean E. Livingston, Co-Founder CNTP and Author Oakville’s Flower: The History of HMCS Oakville

Edit: Peter Dixon, HMCS Haida historian